The building at the corner of Central and Elm Streets in Woodstock, Vermont has always appealed to me, perhaps because my family had a very small role in its long and rich history. Said to have been a station on the Underground Railroad, it was later a center of Vermont’s burgeoning ski industry.

In his History of Woodstock, Vermont, Henry Swan Dana tells us that the house was started, though never completed, by Captain Jacob Wilder in 17941. Wilder was a Revolutionary War veteran born in Lancaster, Massachusetts in 1754. By 1789 he was living in the nearby Town of Saltash (now Plymouth), but he had several business interests in Woodstock including mills on Kedron Brook producing linseed oil and cutting stone. On 21 September 1798 Wilder sold the property with the partially completed house to Titus Hutchinson of Woodstock for $600. The house was in the southwest corner of a lot encompassing twenty square rods, or 2.5 acres.

Titus Hutchinson was the youngest son of Reverend Aaron Hutchinson, a Yale-educated minister and classical scholar who left his church in Grafton, Massachusetts in 1774 to preach as an unsettled minister in the towns of Woodstock, Pomfret, and Hartford. A 1794 graduate of Princeton, Hutchinson opened a law office in Woodstock in 1799. He went on to serve as an Associate Justice on the Vermont Supreme Court, and its Chief Justice from 1831 to 1833. A passionate abolitionist, he was a frequent contributor to the Liberty Party’s Green-Mountain Freeman, their candidate for Governor in 1841 and for Congress in 1843, 1844, and 1846. It is therefore not surprising that he was active in the smuggling of enslaved people from the southern states into Canada.

Several homes in Woodstock are said to have been stations on the Underground Railroad including the Hutchinson house, the Blue Horse Inn at 3 Church Street, and the Ransom Tavern in South Woodstock. Credible support for Hutchinson’s involvement can be found in Wilbur Siebert’s The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom, which lists him in its directory of Underground Railroad operators2 and in Raymond Zirblis’ Friends of Freedom, The Vermont Underground Railroad Survey Report3. According to local lore, there was a tunnel, now collapsed, running from the basement to Kedron Brook through which enslaved people were brought into the house.

Closer examination of the tunnel legend raises certain logical questions. The brook lies about 120 yards southeast of the house and the creation of such a tunnel at any point in time would have been almost impossible to conceal. It would also have entailed crossing land that Titus Hutchinson did not own. That the tunnel may have been a myth or perhaps had nothing to do with the Underground Railroad casts no doubt upon the involvement of the man or his home. A 1976 letter written by Mrs. Clara S. Cooper of Randolph, Vermont observed:

I stayed nights with Sara Hutchinson [granddaughter of Titus] when I was in High School – she had told me about the house being used as an underground slave station. She never mentioned a tunnel but said that the room I slept in was where they kept the slaves during the day and then sent them on toward Canada at night. That room had a long closet with a door at each end and Miss H. said that the slaves used that. I don’t know if it is still there as it has been changed since I used the room (sometime before 1910). That room is the large 2nd floor room on the corner toward the park.” 4

Titus Hutchinson’s son Oramel Hutchinson (1804-1876) is also reliably credited with using his home in Chester, Vermont as a station on the Underground Railroad.

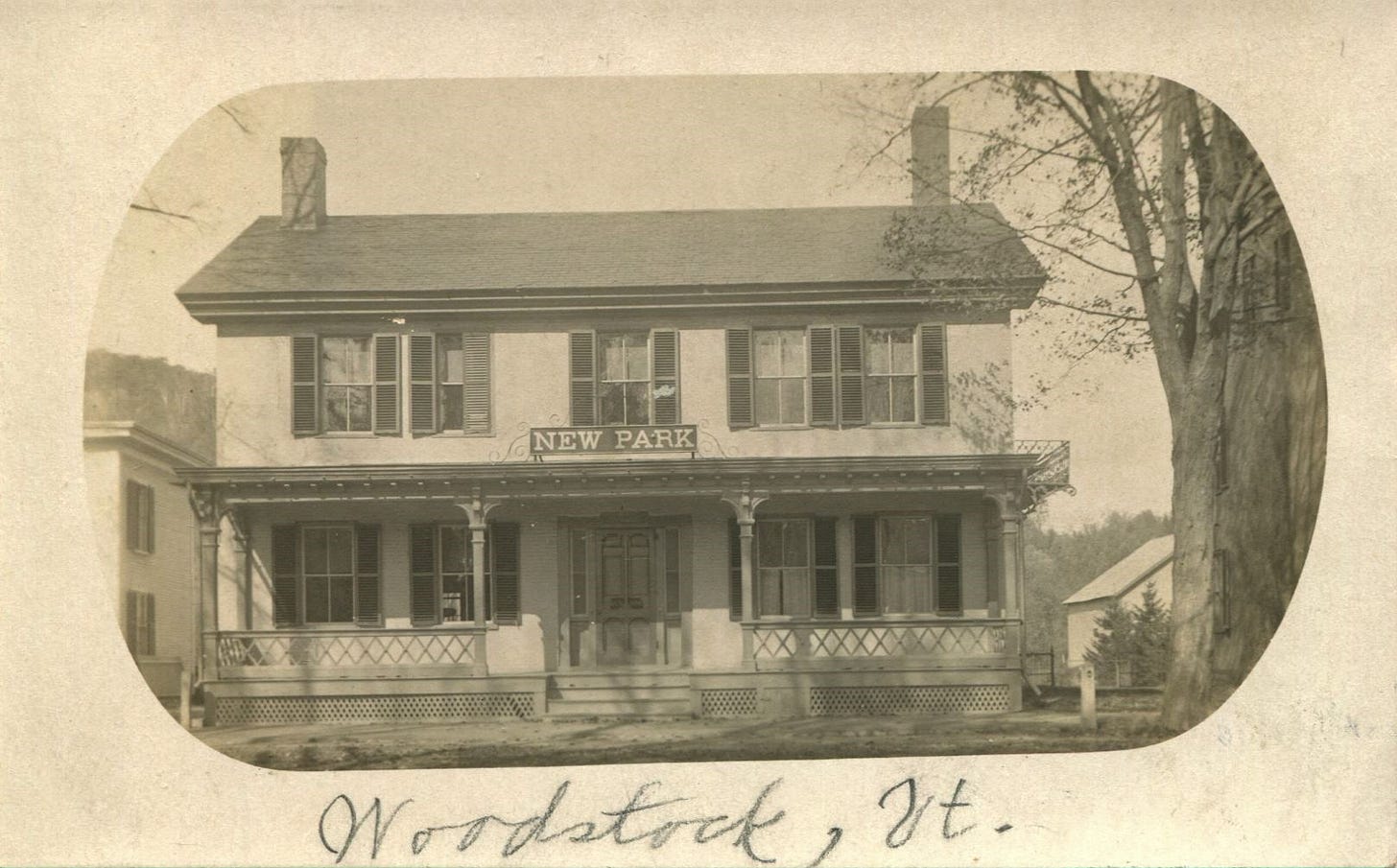

Titus Hutchinson died on 24 August 1857 leaving all his real estate to his three oldest sons, Edwin, Oramel, and Henry. The house passed to Edwin (1803-1861), also an attorney in Woodstock and the executor of his father’s estate. Of the 11 children born to Edwin Hutchinson and his two wives, Eunice Dana (1809-1845) and Harriette Beaman (1824-1852) only three survived their parents. His unmarried daughter Sarah Hutchinson (1849-1927) lived in the house until about 1912 when she was no longer able to care for herself. On 10 January 1925 her guardian, Dr. F. Thomas Kidder, sold the house to Bob and Betty Royce. The Royces had previously acquired the former New Park Inn at 7 The Green in 1917 and had been running it as the White Cupboard Inn. With the acquisition of the Hutchinson House, both properties were combined as an expanded White Cupboard Inn, with the brick building at 7 The Green referred to informally as the “Pink Cupboard”.

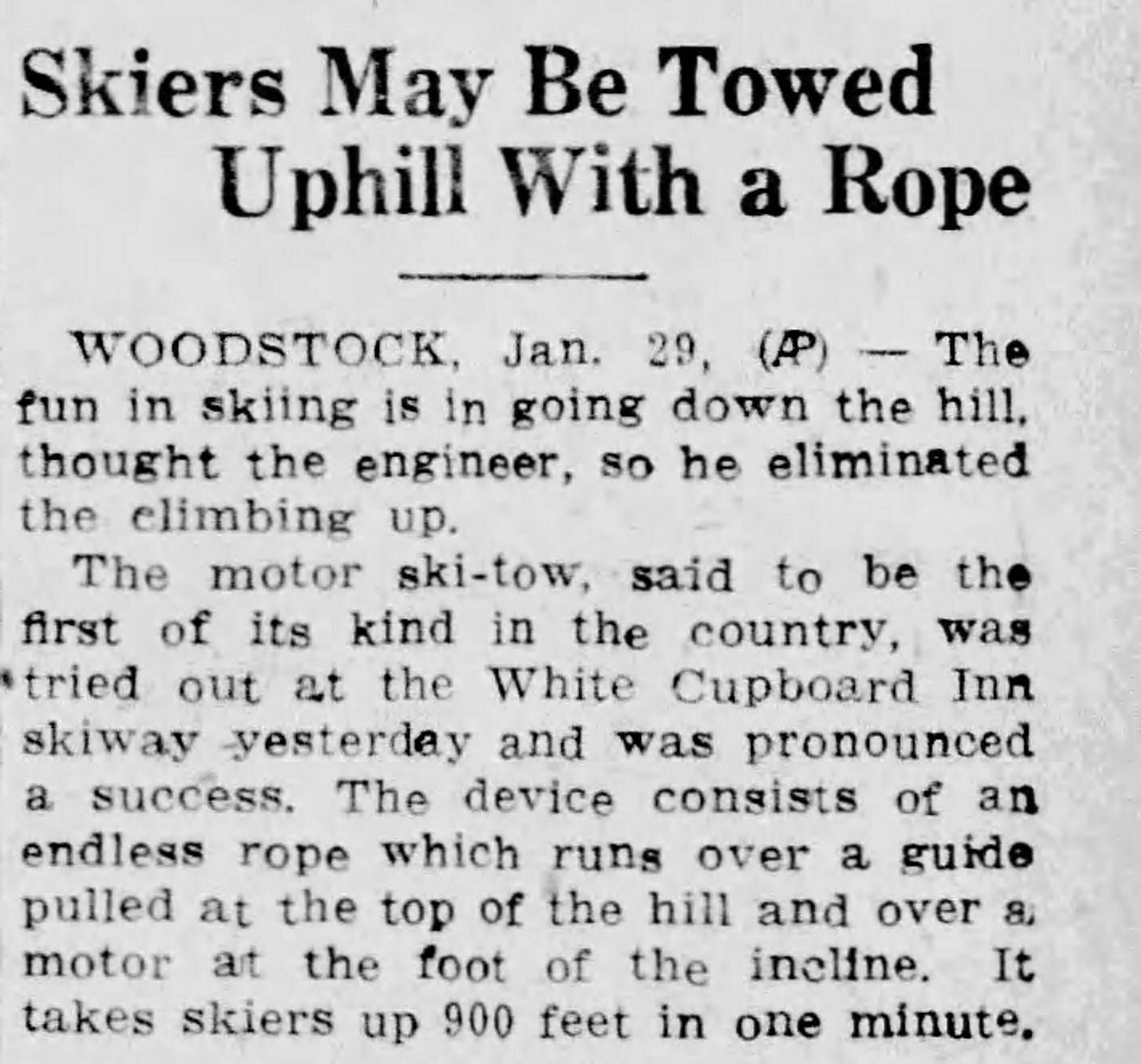

Betty Royce is generally credited with having conceived of the rope tow that was opened on Gilbert’s Hill in 1934. In a 2004 article published in the Rutland Daily Herald Don Wickman notes that the idea of a rotating rope powered by an automobile engine was modeled upon one created by Canadian ski jumper Alex Foster at Shawbridge, now Prevost, Quebec.5

The White Cupboard Inn was badly damaged in a fire on 26 April 1940 that destroyed much of the interior including the second and third floors. In rebuilding, the Royces replicated as much of the original structure as was possible but created one large “dormitory” on the third floor to accommodate about 25 of the young male skiers that were rapidly becoming a target market.

Betty Royce died in December of 1942 and her husband Bob in June of 1943. In September of that year, Bob Royce’s executor sold the White Cupboard Inn to H. Beard and Mary Lou Adams of Detroit, Michigan. In addition to running the Inn, “Beard” Adams was a ski instructor. The Adams subsequently divorced and, in August of 1947, sold the Inn to Norman Craven who, in September, conveyed it back to Mary Lou Adams. On 20 March 1950, Mary Lou Adams sold the Inn to Nelson and Mary Lee.

The Lees had a farm in North Bridgewater and their intent was to provide the Inn with milk from their herd of Jersey cattle, lamb, and produce from an extensive garden. The farm-to-table concept was well ahead of its time but quickly fell victim to the many regulations governing the food service industry and, quite probably, the marginal profitability of the business itself. On 13 November 1955, the Lees sold the Inn to Allan Darrow, then the general manager of the Woodstock Inn. Darrow left his position at the Woodstock Inn in order to run the White Cupboard, and also managed the Plymouth Notch Inn at the Coolidge Homestead. In August of 1967, the Inn’s liquor and operating licenses were revoked by the Vermont Liquor Control Board for non-payment of the rooms and meals tax. The order was rescinded shortly thereafter, but it might be inferred that the business wasn’t faring any better under the Darrows’ management than it had the Lees’.

In 1967 both the Hutchinson House and the adjacent Benjamin Mower House were acquired by Laurance Rockefeller, who donated them to the Woodstock Historical Society for use as income-producing properties. Despite initial consideration of continued use as an inn and a restaurant, the building now contains an art gallery and a consignment shop on the first floor. Given the prior owners’ struggles to keep the business alive, Rockefeller’s vision and generosity were probably the best possible outcome and ensured that these architectural gems would continue to grace The Green for generations to come.

Henry Swan Dana, History of Woodstock, Vermont (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1889) 155.

Wilbur H. Siebert, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (New York and London: The Macmillan Company, 1898) 435.

Raymond Paul Zirblis, Friends of Freedom the Vermont Underground Railroad Survey Report (Vermont: The State of Vermont, Vermont Department of State Buildings, and Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, 1996) 66.

Mrs. Clara S. Cooper (Randolph, Vermont) to Mrs. Dorothy Cook, letter, 26 December 1976, collection of the Woodstock History Center.

Don Wickman, “Upwardly Mobile.” Rutland Daily Herald, March 18, 2004, C1.

And Oh if my grandmother was alive -- how she would love this post! As the former Snow Queen of Suicide Six, she regaled us with stories about the first rope tow. I will ask mom if she can find any old pictures or recount the stories!

What relevant color you have brought to the Woodstock Green! My first Woodstock office was in the Inn -- up on the second floor with Janine Williamson, Mary Ellen McCue and Jon Weber. What fun it would have been to share the stories of the active abolitionists as I handed out endless Holiday cookies and balanced vats of sloppy cider and syrupy eggnog up and down the stairs and through the gallery for Wassail weekend....

What really piques my interest is the possibility that it was a station on the Underground Railroad. While the legend of the tunnel running from the basement to Kedron Brook may have been debunked, there's no doubt that Hutchinson and his family were active in smuggling enslaved people from the southern states into Canada. Imagine fleeing to Canada with a stop on the Green and running this effort in such an exposed location -- talk about courage and determination!

Oh if the walls and Titus could talk! I will never pass by it again without remembering its rich history and that the fight for equality is ongoing, and we must continue to challenge systemic oppression wherever we see it.