Anyone with an interest in history has probably thought about how that interest came about, and how it shaped the person they became. Even as a child, when summers were eternal and time was purely an abstract concept, I was fascinated by the thought that other people had been here before me. It wasn’t “history” in the sense embodied by Plymouth Plantation or the sites along Boston’s Freedom Trail, those were famous people and places, either carefully preserved or replicated. What fascinated me were the people and the places that hadn’t been considered worthy of study or preservation, like the cellar holes that dotted the landscape of my grandparents’ farm in North Bridgewater, Vermont. Of that world, all that remained were seemingly endless stone walls, scattered foundations, and a little cemetery at the bottom of the hill. My brother and I spent hours exploring the cellar holes and the graveyard, and I still remember the stories sculpted in slate and marble:

“Here are deposited the remains of Deac. Joseph Perkins born in Lyme, Con. May 17, 1760 killed by the fall of a tree June 6, 1824.”

“Mrs. Sarah Winslow died Oct. 8th 1807 AE 67 y. Death is a debt to nature due. I’ve paid this debt & so must you.”

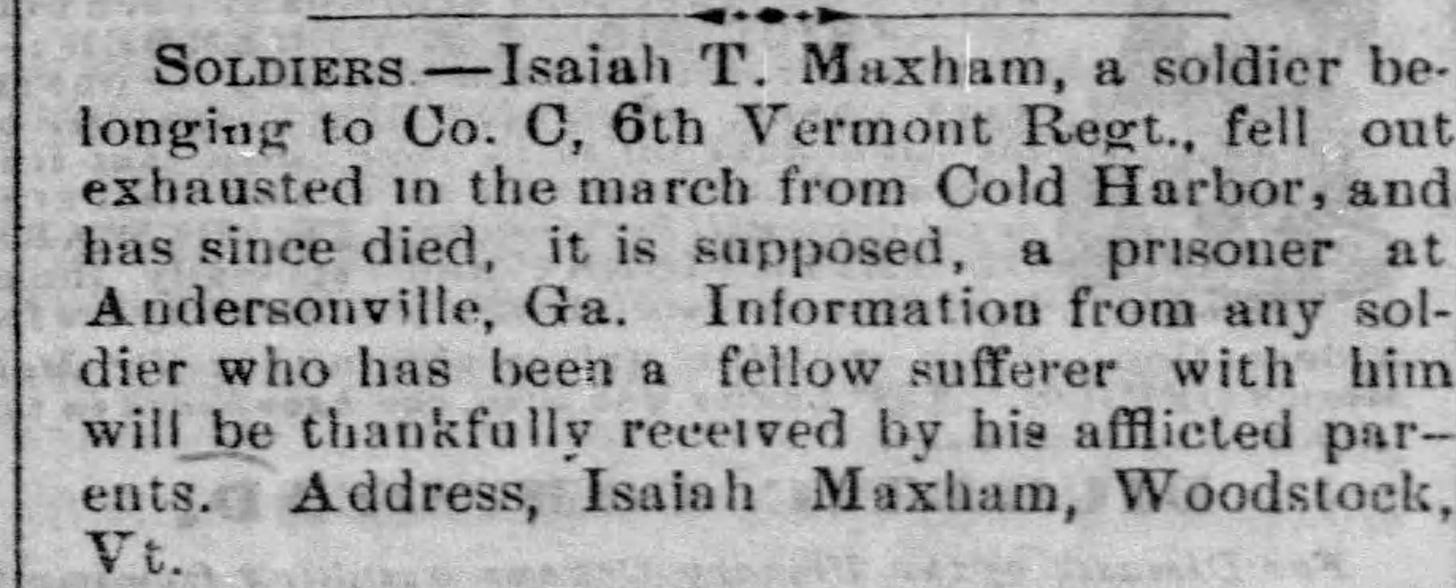

The stone that fascinated me most, however, read “Isaiah T. Maxham Co. C 6th Vermont Vol. Taken Prisoner Near Cold Harbor Va. June 15, 1864. Died at Andersonville Ga. Sept. 11, 1864. AE 22 yrs. 1 Mo.”

It was here in this little cemetery as a young boy that I first sensed a relationship between time, place, and people. The Civil War, an interest of mine even then, had actually reached all the way from Georgia to a little hamlet in central Vermont. In later years I would come to understand that the war reached virtually every little hamlet in Vermont and in the nation as a whole. Somehow that realization brought a new dimension to a landscape that had always seemed relatively immutable. Where had Isaiah T. Maxham lived? Had he attended school in the little one-room schoolhouse at the top of the hill? What did this hillside look like when he made his way down this same dirt road on a September day in 1862, beginning the journey from which he would never return?

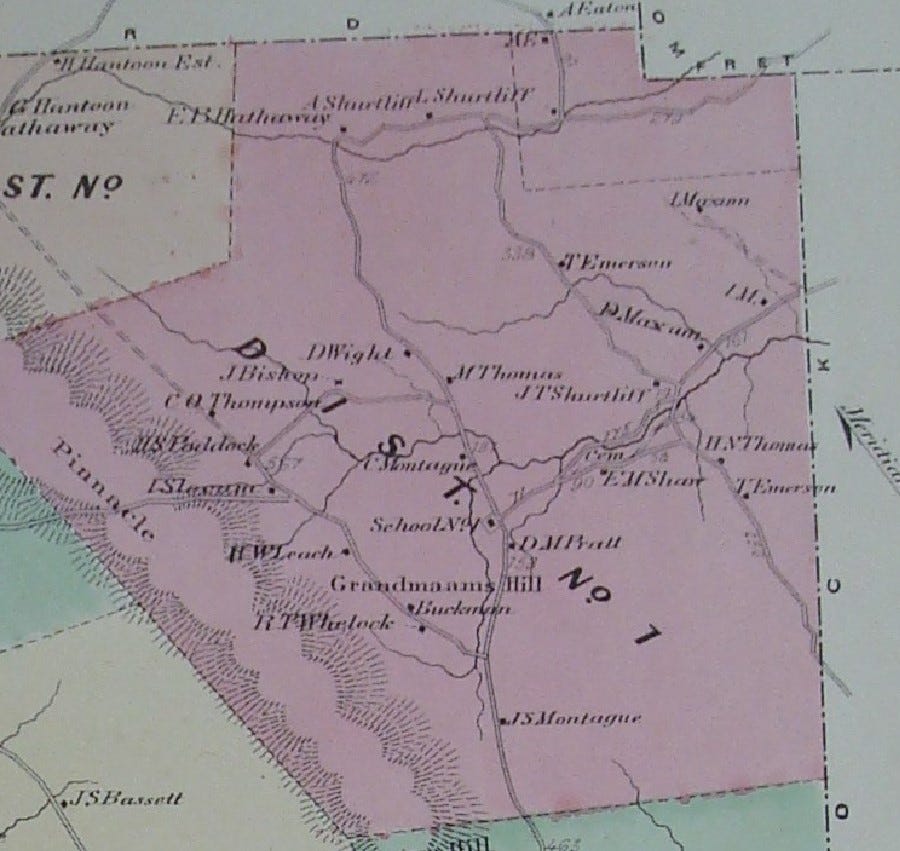

Isaiah Thomas Maxham was born on 1 August 1842 in Bridgewater, Vermont, the only surviving child of Isaiah and Mary (Holmes) Maxham. The senior Isaiah was a farmer living on North Bridgewater Road about half a mile east of the cemetery. The 1860 Federal Census lists the members of the household as Isaiah Maxham (58), his wife Mary (56), son Isaiah T. Maxham (18), a cousin, Jabez R. Maxham (18), and Mary’s unmarried sister Ruth Holmes (52). Isaiah T. Maxham and Jabez R. Maxham were day hands and they presumably helped on the 110-acre farm that straddled the Bridgewater-Woodstock line.

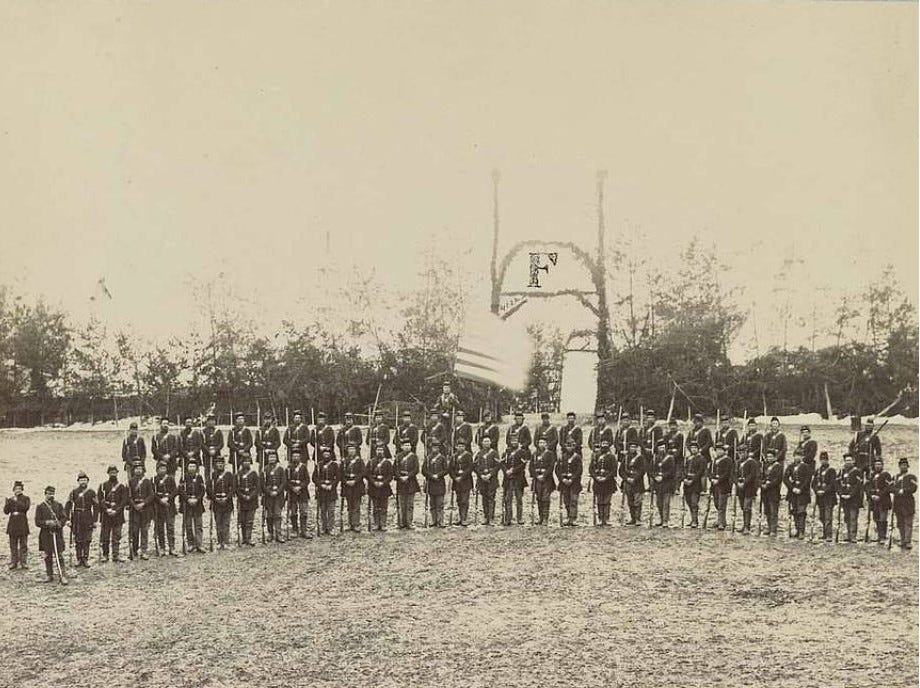

On 26 August 1862 Isaiah T. Maxham, then 20 years old, enlisted as a private in Company C of the 6th Vermont Infantry. Army regiments of the time typically consisted of ten companies, each with 97 men and three officers. Each company was recruited regionally, with Company C comprised of men from Windsor County. Eight of them, including Isaiah, came from Bridgewater1. The regiment had been raised on 16 September 1861 and rushed with only a month’s training to Camp Griffin in Lewinsville, Virginia, where they joined the Vermont Brigade. The 6th Vermont had been at war for a full year and was a battle-hardened force by the time Isaiah was mustered in on 30 September 1862.

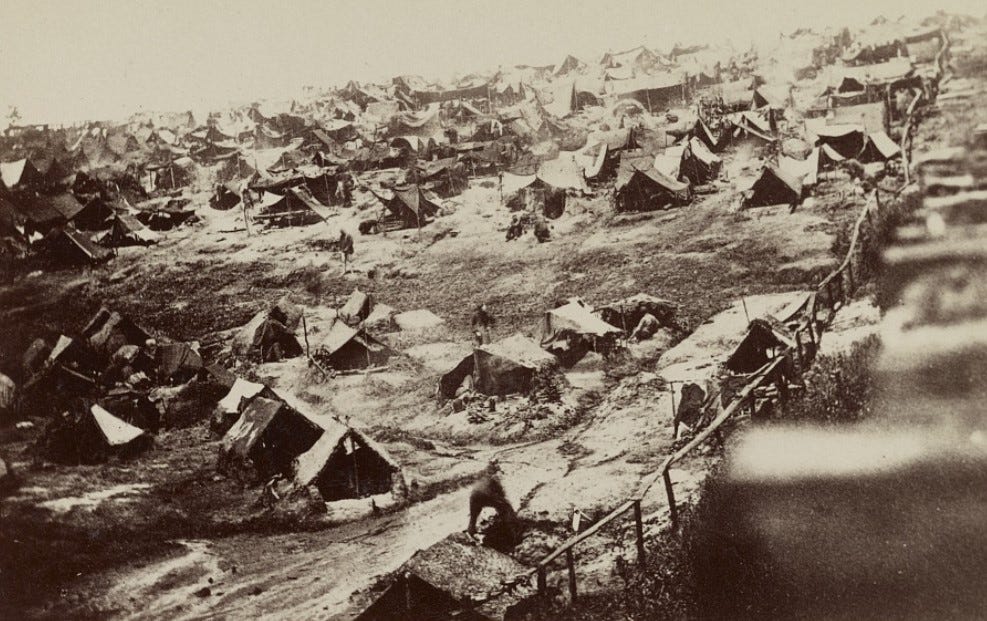

Isaiah reached the regiment in time for the Battle of Fredericksburg in December of 1862, fought with them at Gettysburg in July of 1863, and at the Battle of the Wilderness in May of 1864. Exhausted, possibly ill, and unable to keep up, he fell out of the ranks at Cold Harbor, Virginia, and was captured on 15 June 1864. Taken to Andersonville Prison, he died of disease on 11 September 1864, less than three months after his arrival. He’s buried in the military cemetery there and the stone in North Bridgewater Cemetery is simply a memorial.

I didn’t learn the rest of the story until many years later. Isaiah’s father advertised in Vermont newspapers for anyone who might have knowledge of his only son’s fate. If he heard from anyone who had been with his son at Andersonville, there’s no known record of it. Isaiah’s fellow Bridgewater residents Levi F. Wilder and James E. Sawyer, both of Company H, 11th Vermont Infantry, died there on 2 August 1864 and 10 February 1865, respectively.

Isaiah Maxham Sr. survived his son by only five years, dying in Bridgewater at age 68 on 22 December 1869. He’s buried in the North Bridgewater Cemetery alongside his parents, Isaac and Ruth, a daughter who died as an infant, and the memorial stone for his son. His will, written on 10 July 1866, awarded his wife Mary the sum of $1,000 and divided his real estate and personal property equally between Mary and her sister Ruth “provided, however, that the said Ruth Holmes shall live with me and do what she is able, or her health will permit towards taking care of myself and my wife Mary Maxham during our natural lifetime.”

On 31 October 1871 Mary (Holmes) Maxham and her sister Ruth Holmes sold Isaiah Maxham’s 110-acre farm to Edwin F. Thompson of Woodstock for $2,250. Thompson owned the farm immediately east of the Maxham property and the purchase price was about what Isaiah Sr. had paid for the farm when he purchased it in 1838.

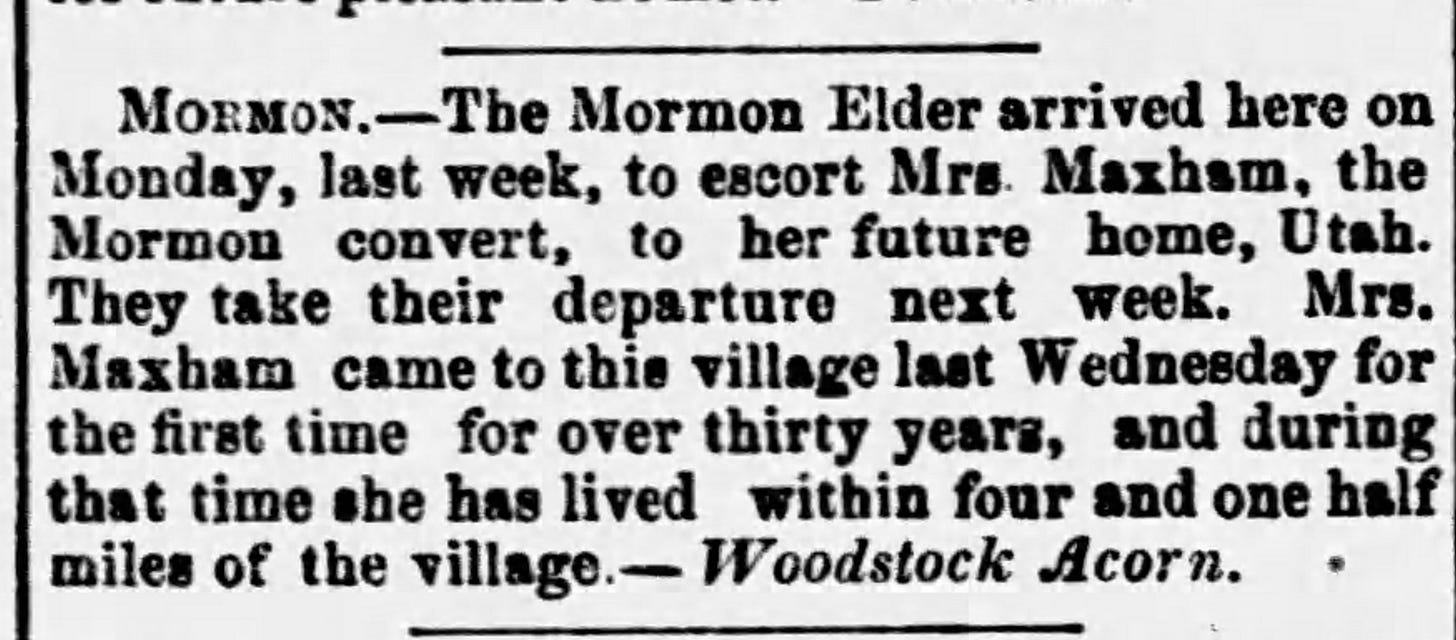

In May of 1872, a Mormon elder arrived in Woodstock to escort Mary (Holmes) Maxham and her sister Ruth to Utah. This part of the story raises more questions than answers.

The thought that Mary (Holmes) Maxham and, quite probably, her sister Ruth, had lived on the farm for more than three decades without making the four-and-a-half-mile trip to Woodstock is staggering and may explain how two elderly Vermont women came to embrace a faith that must, despite its Vermont origins, have been quite foreign to both the extended Maxham and Holmes families. Were they approached by missionaries making their way from farmhouse to farmhouse? Was their conversion a response to a lifetime of isolation and perhaps unhappiness? The questions may be unanswerable at this point. Their journey across the country, presumably by way of the transcontinental railway that had been completed only three years before, must have been both awe-inspiring and terrifying for two women cut off from the world for so long. It may have been too much for Ruth, who died shortly after her arrival in Lynne, Utah on 25 August 1872. She was 65 years old. Mary (Holmes) Maxham died in Lynne on 30 July 1877 at age 75. She’s buried in Ogden, Utah’s City Cemetery, some 2,400 miles from the little cemetery on the Vermont hillside where her husband and children lie.

Theodore S. Peck, Adjutant-General, Revised Roster of Vermont Volunteers and Lists of Vermonters Who Served in the Army and Navy of the United States During the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1866 (Montpelier, VT: Waterman Publishing Company, 1892), 189-192

I don’t really know where to start, so I’ll start with the brilliant line, “we really are the Frasier and Niles Crane of our time.“

I am stunned by how little I know of our American Civil War history. My parents deserve a refund on their Choate And Dartmouth tuitions

Your research, and that of your cohorts, is absolutely fascinating. It’s astounding how much history can be found if one looks hard enough, and literally under every rock, and inside every nook and cranny. Genealogical records can show you so much.

Please keep on being the Curious Yankee, so that I can keep learning.

I almost forgot your other brilliant line: “no, penicillin, won’t take care of it.” You are too much!

Great article. Those fields, stone walls, and cellars were my first introduction to the brief nature of human life. Another stone in the same graveyard bears the well known inscription

Remember me as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I,

As I am now, so you must be,

Prepare for death and follow me.

Your article led me to do a little research on this verse, which is an interesting sidebar to your work. Apparently “graveyard people” (there must be a word for those interested in the study of graveyards) are attempting to locate every tombstone in New England bearing this inscription in order to date its earliest use in America, as yet unknown. The commonality of the verse increases greatly after 1863, perhaps reflecting the changing social attitudes towards death caused by the far reaching effects of the civil war. It will be interesting to check the date on the stone in N. Bridgewater in this regard. A brief internet perusal of the history of the verse opens yet another rabbit hole!

I enjoyed your work as always.