History isn’t always advertised by roadside markers. Sometimes we have to look for it, but even the most prosaic structure has a past and a place within the larger context of human development. So it is with Western Avenue Studios, a rambling brick mill complex at the east end of Western Avenue in Lowell, Massachusetts. It’s a down-at-the-heels section of a city struggling to reinvent itself, with an eclectic assortment of auto body shops, breweries, and artist studios occupying space built for, and long since vacated by, the American textile industry.

The Studios’ tired surroundings obscure a rich social and technological history. It sits on the edge of the Pawtucket Canal, constructed in 1796 to facilitate the shipment of lumber around Pawtucket Falls on the Merrimack River. The completion of the Middlesex Canal about a decade later rendered the Pawtucket Canal commercially obsolete. In 1821, the Merrimack Manufacturing Company purchased the canal’s charter, widened and deepened it, and repurposed it as a power source for the textile industry in what would soon become the first planned industrial city in the United States.

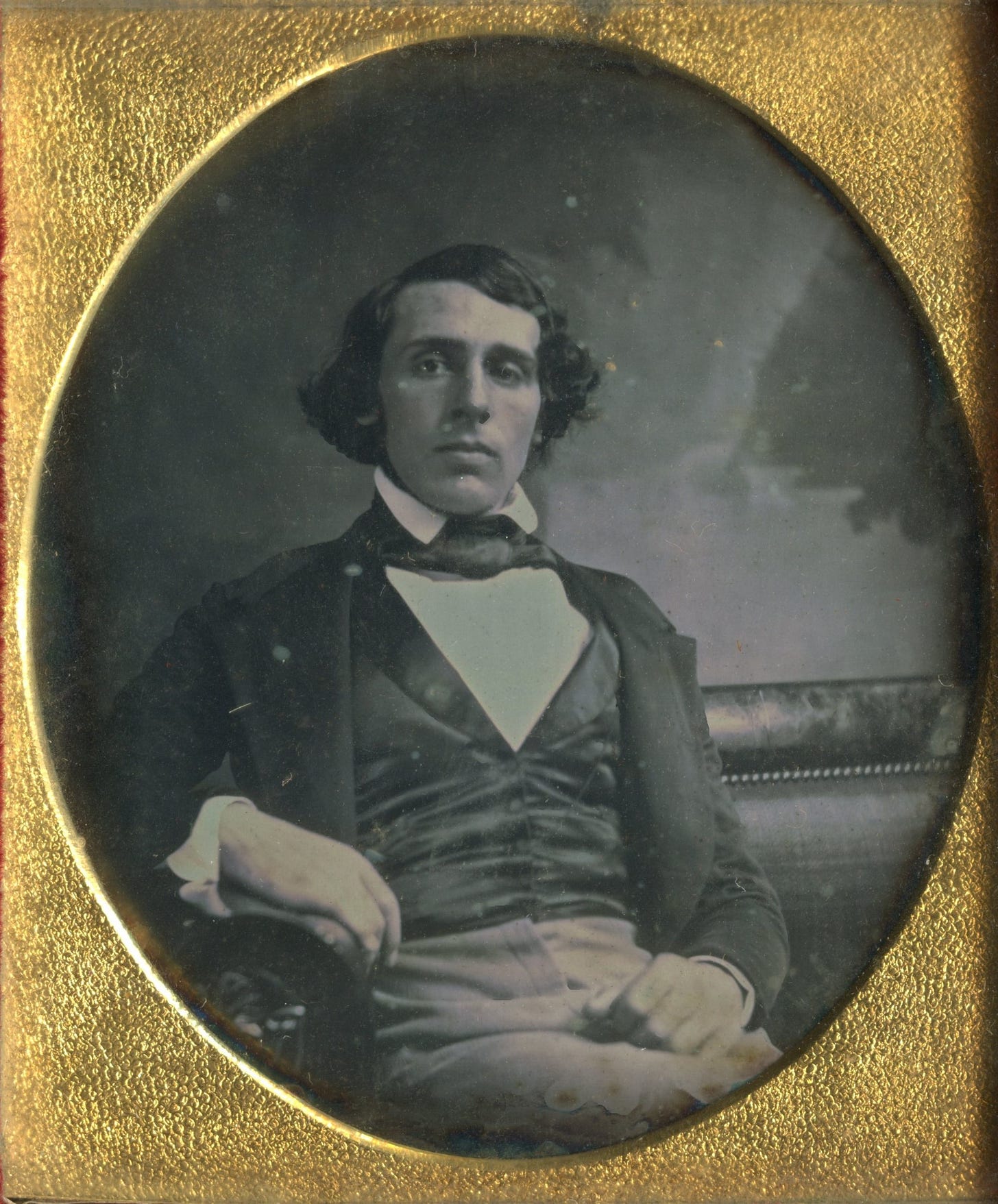

The larger story of Lowell, its mill girls, and the birth of the American Industrial Revolution is well known, but what of these particular buildings? Why were they built, when, and by whom? That story has its roots some 65 miles southwest of Lowell in the little Worcester County community of West Brookfield, where, on 1 February 1820, Henry Penniman Bliss was born. Bliss was the oldest of eight children born to Jesse Bliss, a Dartmouth-educated attorney, and his wife, Mary Penniman. While not poor, neither were they notably wealthy, and it is perhaps telling that three of Jesse and Mary’s four sons became merchants.

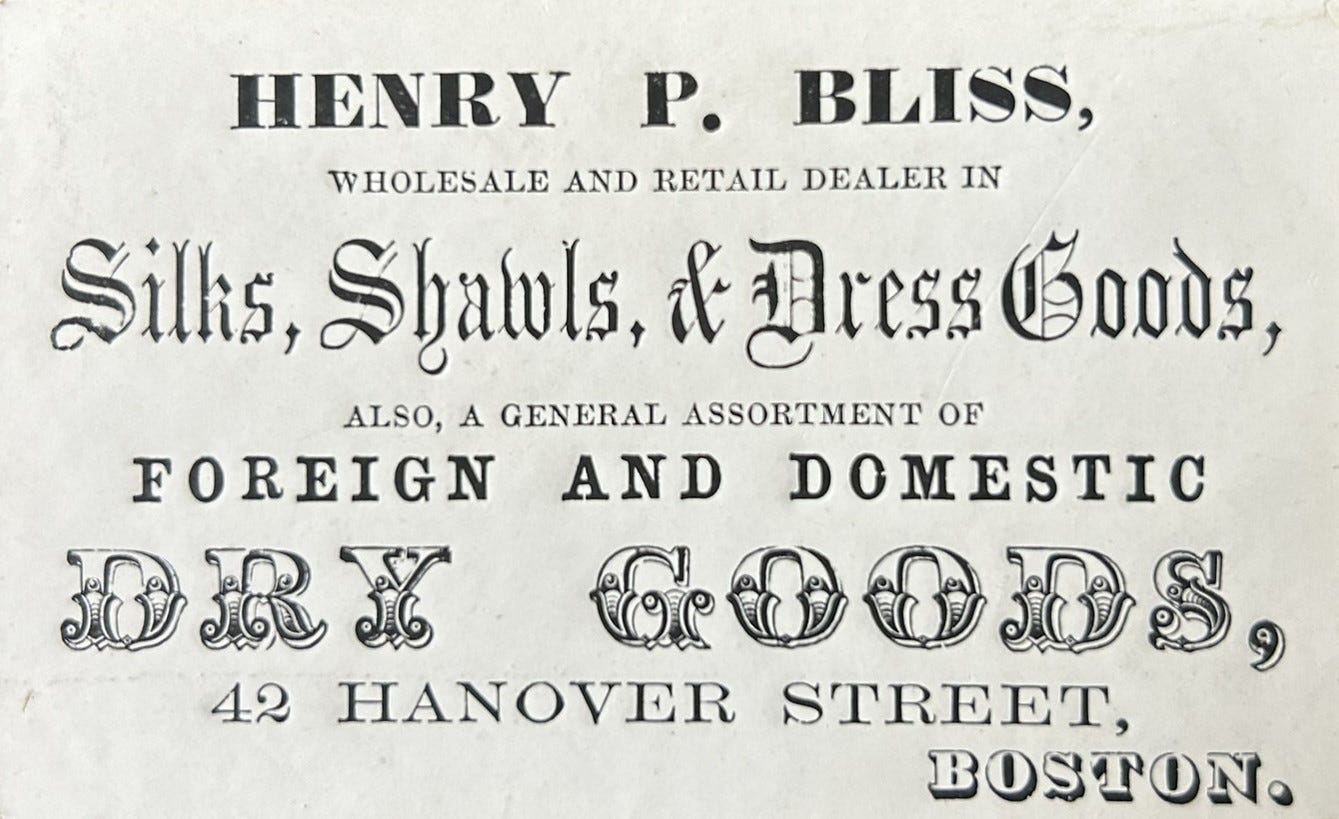

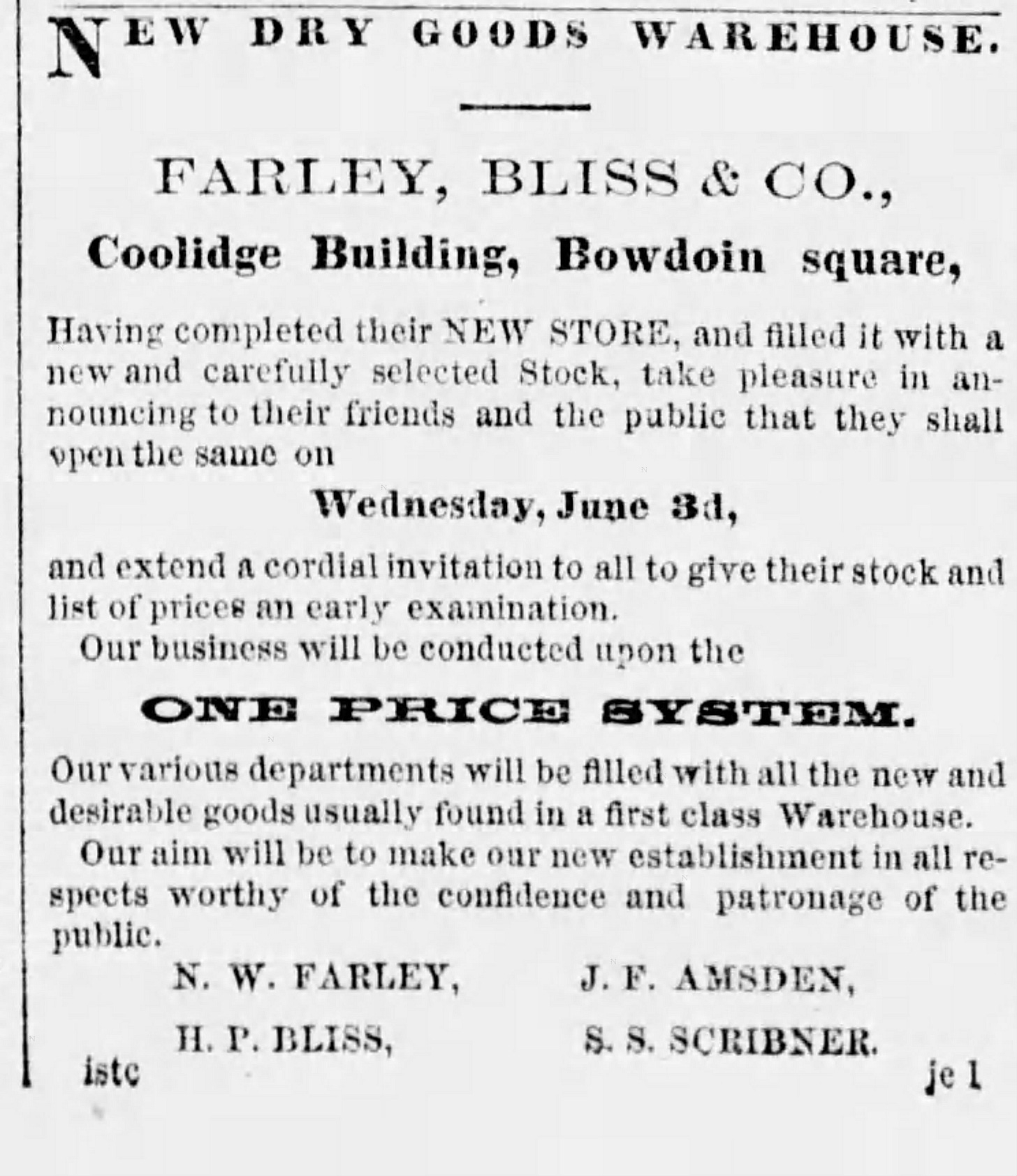

I’ve found no evidence that Henry, or “HP” as he was known, attended college. His obituary tells us that he left West Brookfield for Boston at age 18 and was in the dry goods business by age 20 (1840). Dry goods encompassed fabrics, lace, and ready-made clothing. In 1845, HP married Hannah Laurinda “Laura” Warren of Grafton, Massachusetts. The Warren family also had an entrepreneurial streak- Laura’s brother Samuel Dennis Warren would create the S. D. Warren Paper Company of Westbrook, Maine, in 1854. The couple settled in Cambridge, with HP operating his dry goods business across the Charles River in Boston. He did business initially as H. P. Bliss & Company, later as Farley, Bliss & Company, and, after 1861, as Cushing & Bliss.

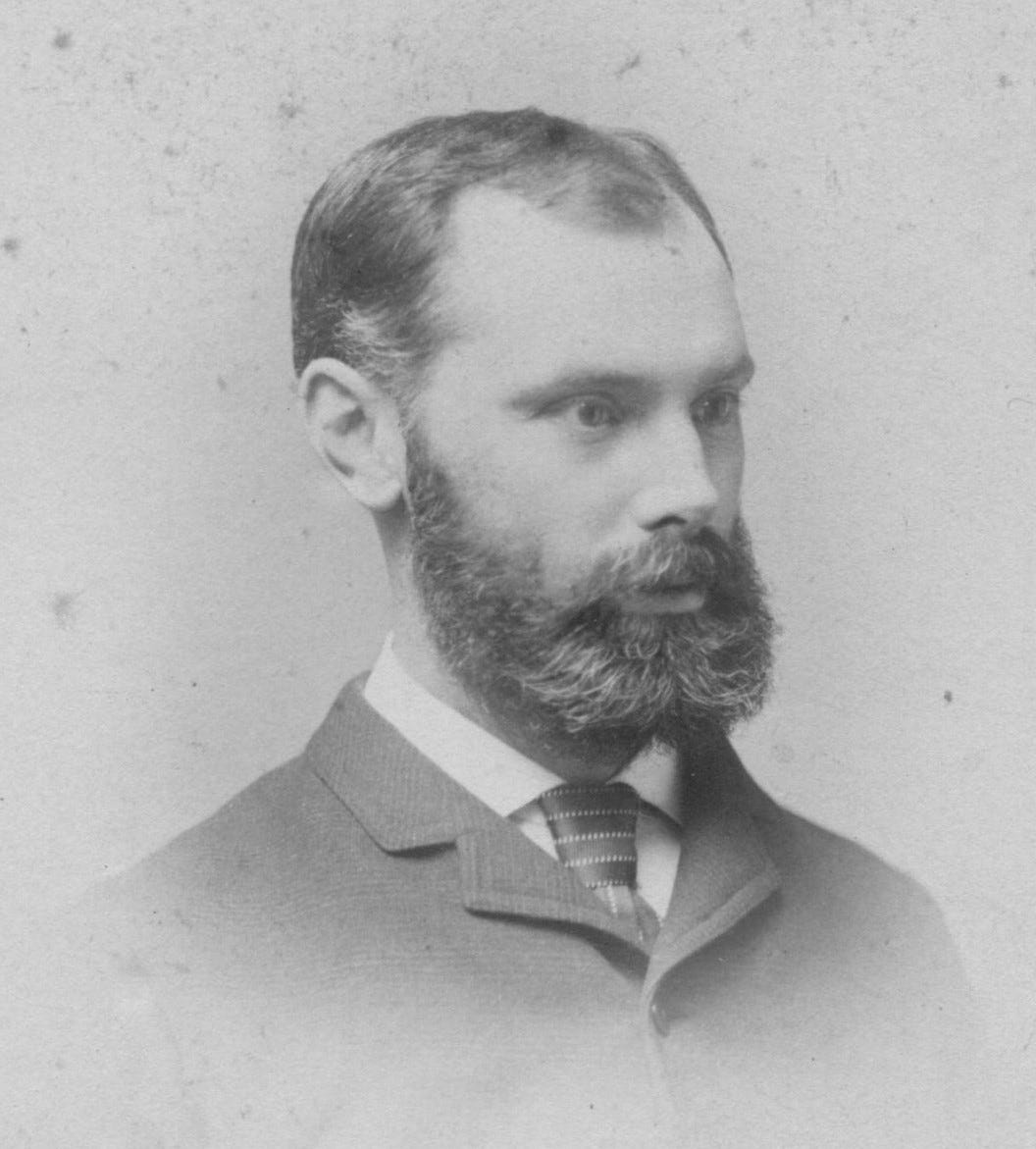

After Laura died in 1849, HP married her older sister, Delia Warren, with whom he had two sons: Edward Penniman “EP” Bliss and Henry Warren “HW” Bliss. EP attended Harvard College with the ambition of becoming a writer.

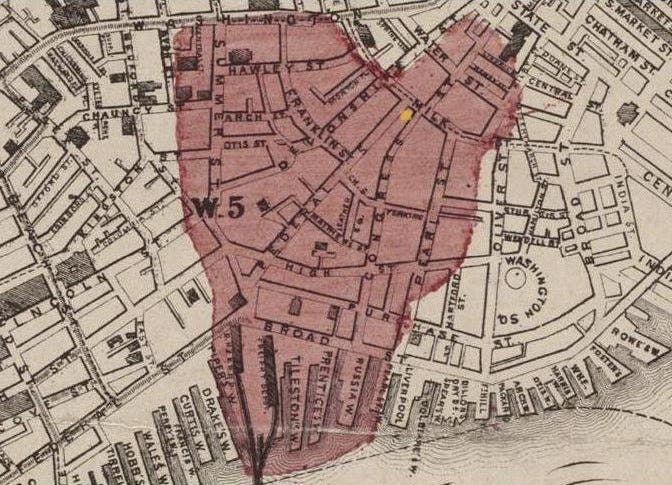

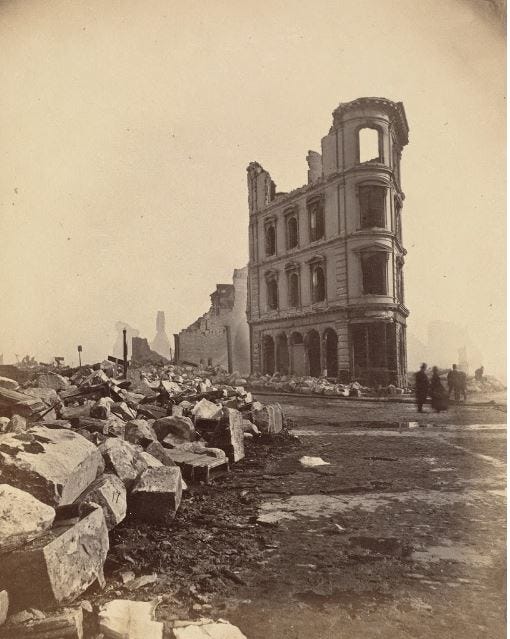

In November of 1872, during EP’s senior year, fate intervened in the form of the Great Boston Fire. Cushing & Bliss, located at 55 Milk Street (the yellow dot on the map below), was near the center of the burn zone and almost certainly destroyed.

The company’s reported loss was $75,000, compelling EP to set aside his literary ambitions and join his father in rebuilding the business immediately upon graduation in June of 1873.

In 1884, EP’s younger brother, Henry Warren Bliss, graduated from Harvard and joined his father and older brother at Cushing & Bliss.

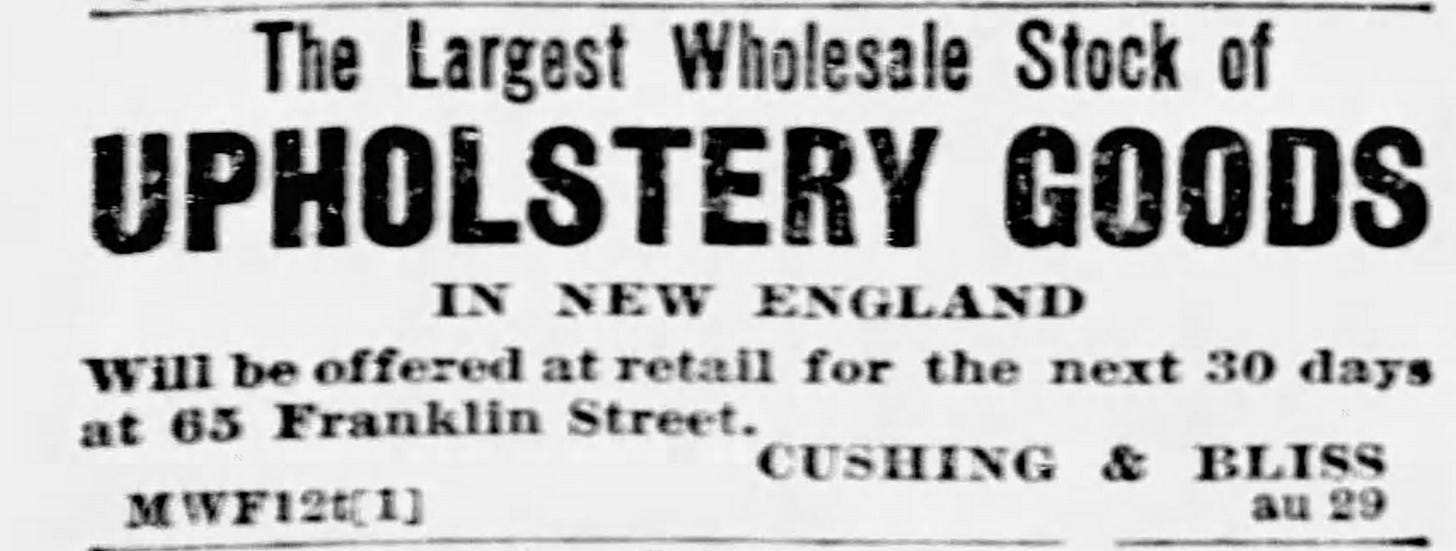

With his two sons running Cushing & Bliss, HP retired from the business in 1886 and died ten years later. The firm appears to have prospered as, by 1898, it was advertising the most extensive wholesale stock of upholstery goods in New England.

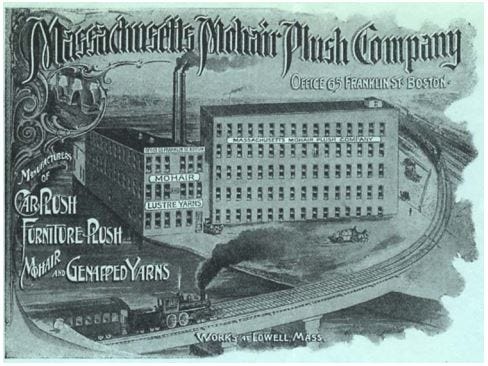

In 1891, the Bliss brothers established the Massachusetts Mohair Plush Company with EP as President and HW as Treasurer. The company had a Boston office at 65 Franklin Street and a 100-loom mill on Western Avenue in Lowell. Mohair is a high-quality textile known for its sheen and durability. Woven from the hair of Turkish Angora goats, it was used extensively in the upholstery of furniture, carriages, railroad cars, and later automobiles.

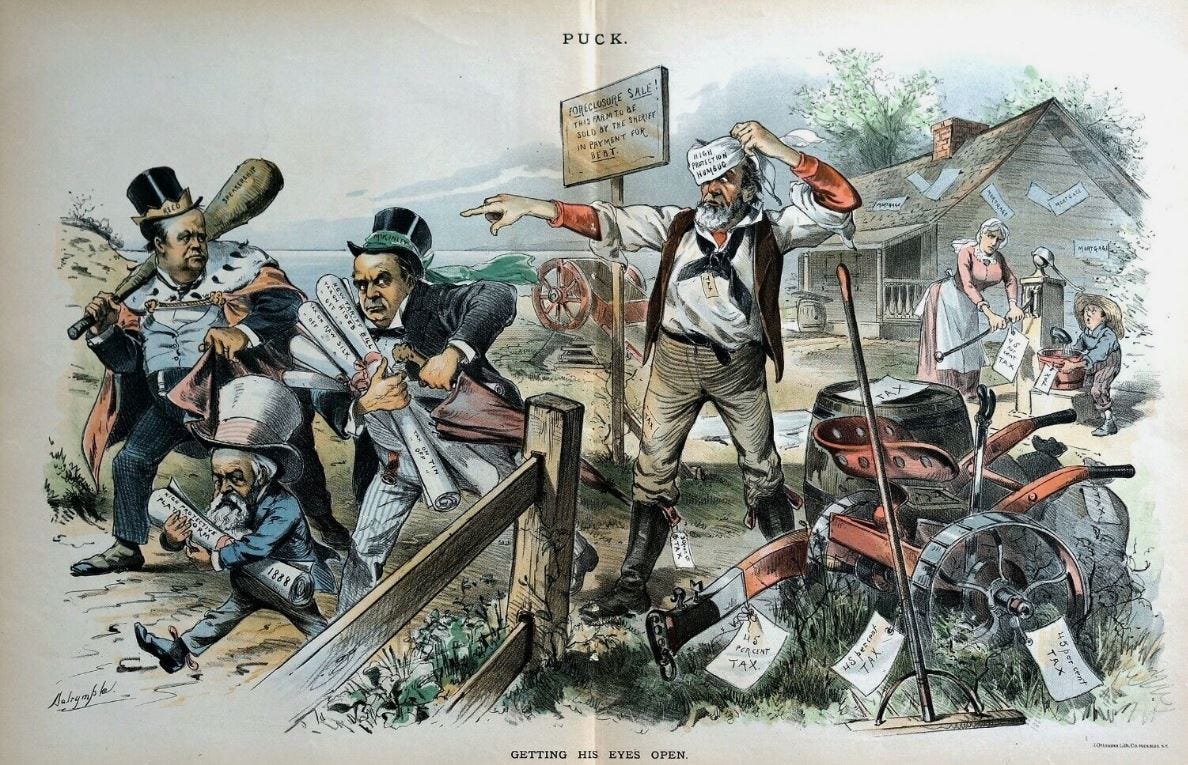

Why would two brothers with a successful dry goods business decide to open a textile mill at a point when most of Lowell’s mills had been in existence for half a century or more? The decision appears to have been a response to political circumstances. On 1 October 1890, Congress passed the McKinley Tariff Act, which substantially increased duties on virtually all imported goods. The Republican Party, led by President Benjamin Harrison, favored the additional Treasury revenue and the protection of American manufacturing interests, while the Democrats (and, as it turned out, the nation as a whole) opposed the significant price hikes that ensued.

I expected to find the Bliss brothers, whose stock in trade consisted mainly of imported fabrics, opposed to the highest tariff rates in American history. That was not the case. While generally sympathetic to the Democratic Party positions of the day, EP and HW Bliss saw the tariff as a business opportunity. In an 1891 interview published first in the Lowell Citizen and later in the Fall River Daily Evening News, mill superintendent George S. Poole noted that mohair fabric had previously been woven on hand looms in Germany, where a skilled weaver could produce two yards a day. One of the mill’s 100 machine looms could produce 16 yards daily. Poole added, “The McKinley bill has raised the duty on these goods about 20 percent and has made an American market without which our company would never have started in business.”1 The Massachusetts Mohair Plush Company wasn’t a departure from their retail business but a diversification, with the textiles produced at the Lowell mill sold through Cushing & Bliss.

The Massachusetts Mohair Plush Company exhibited its products at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and it won a medal for its exhibit of a plush loom invented by George Poole.

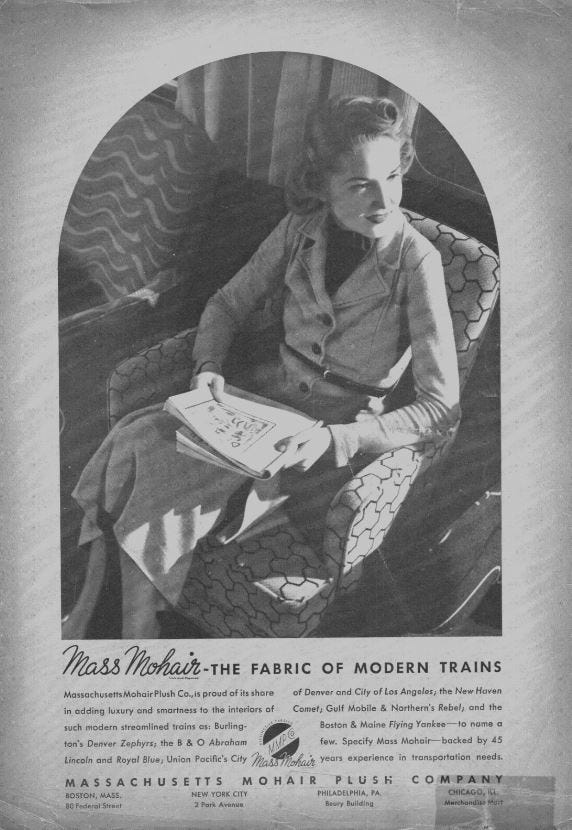

EP Bliss died on 22 March 1916, leaving no children. In March of 1917, HW’s son, Henry M. Bliss, graduated from Harvard and went to work in the mill’s sorting room. Within a month, his career was interrupted by America’s entrance into World War I. He would return after the Armistice, serving as the company’s Vice President by 1937 and, by 1941, as its President. HW’s son-in-law, Austin B. Mason, joined the company as Treasurer in 1919.

Cushing & Bliss continued as a retail business until at least 1901 and remained as the sales agent for Massachusetts Mohair products until after 1926. The Massachusetts Mohair Plush Company prospered to the extent that a second mill was established at Salmon Falls, New Hampshire, in 1944, and the company had contracts with railroads and several automobile manufacturers, including Chrysler. Nevertheless, they were a late entry into an industry already in regional decline when they were established. By the 1890s, the New England textile industry had been outpaced by the South, which offered closer proximity to raw materials (cotton) and significantly lower labor and heating costs. The first half of the 20th Century saw a steady stream of textile manufacturers leaving New England for places like North Carolina. The second half of that Century saw the advent of synthetic fabrics and the opening of foreign markets with still lower labor costs.

President Henry M. Bliss sold the Massachusetts Mohair Plush Co. to New York real estate developers George and Ernest Horvath in 1952. The Horvaths bought up other mill properties in Lowell and elsewhere, along with the water rights to the Lowell canals, using funds borrowed from the Teamsters Union pension fund, the Catholic Archdiocese of Boston, and the Union National Bank of Lowell. They closed the Salmon Falls plant in 1956, relocating both the Lowell and Salmon Falls looms to Kings Mountain, North Carolina. In 1957, a large part of the Western Avenue plant was re-sold to Joan Fabrics, which continued to produce automotive upholstery until it filed for bankruptcy in 2001. The Massachusetts Mohair Plush Company eked out a much-reduced existence as a tenant in Lowell’s Massachusetts Mills and later Boott Mills but appears to have been used primarily as security for the Horvath’s burgeoning debt. Eventually, the overextended Horvaths also filed for bankruptcy. Their Lowell assets were acquired by Corporation Investments, Inc. (CII), a group of local businessmen seeking to protect the existing tenant base and the Union National Bank.

CII subsequently partnered with General Electric to create a hydropower plant at the same bend in the Merrimack River that the Pawtucket Canal was created to bypass in 1796. In 1985, the Lowell Hydroelectric Project was sold to Enel Green Energy for $16,000,000.

In 2004, the vacant Massachusetts Mohair Company mill was acquired by Vespera Development of Stamford, Connecticut, with the intention of converting it to residential apartments or condominiums. When the proposed redevelopment fell apart, developers Karl Frey and Justin Mandelbaum began leasing the space to artists displaced by the wave of redevelopment and escalating rental rates sweeping eastern Massachusetts. Perhaps they recognized an opportunity in an otherwise undesirable turn of events, as did the Bliss brothers more than a century before. In 2023, Western Avenue Studios, the largest artist community in the United States, was bought by the Arts & Business Council of Greater Boston for $20,000,000.

Fall River Daily Evening News 30 October 1891.

Brilliant! Such a masterful job of weaving together sources into a compelling narrative. And I especially appreciate learning about the McKinley Tariff Act given today’s politics. Thank you