The first half of the 19th Century offers fertile ground for the curious researcher. Science was still in its infancy, and medicine in Vermont was largely unregulated. The state’s first medical school, Castleton Medical College, was not established until 1818, and the title of doctor did not necessarily imply actual medical credentials. Many so-called doctors were more akin to tradesmen, dispensing concoctions ranging from botanic remedies to less wholesome combinations of opium and alcohol.

One of the most colorful “doctors” of that era was “Sleeping Lucy” Cooke, a trance medium who made medical diagnoses and set broken limbs while in a hypnotic state from which she claimed to remember nothing. Lucy’s story has been well told by others, including Mark Bushnell in his Hidden History of Vermont1 and Paul Heller in the Barre-Montpelier Times Argus2. Yet, she is sufficiently interesting to merit another look.

Born in North Calais, Vermont, on May 4, 1819, Lucy was the fourth child of Luther and Lucy (Burnham) Ainsworth.

Most of what we know of her early life comes from an autobiographical poem, The Morning of Life, apparently written as a promotional piece in October 1884. In it, she alludes to a financial reversal that occurred when she was eight, forcing the nine Ainsworth children to leave home and be put to work. Probate records indicate that her father, Luther Ainsworth, had borrowed $100 from his father, Jacob, who in turn bequeathed the note to his wife in lieu of dower rights.3 Jacob’s death in 1828 probably forced the sale of Luther’s home to satisfy the debt. Her formal education over before it had begun, eight-year-old Lucy was farmed out as a laborer, first weaving straw bonnets and later as a tailor’s apprentice.

At some unspecified point, probably in the 1830s, Lucy became seriously ill. Allegedly in an altered state of consciousness, she asked for various herbs and roots with which she later claimed to have cured herself.

“Too ill to go further, I lie upon a sick bed several months, am given up to die by three physicians; but finally falling into an unusual sleep, in a dream-like state, a suggestion comes, in an unaccountable manner, of healing by certain roots and herbs prepared in a certain manner. I awake (not having spoken for six months and at times greatly distressed if I attempted to whisper,) and call aloud for some friend, requesting these articles be got and prepared. With much doubt as to the benefit of these drinks, my friends administered these draughts; from which time I steadily improved…”4

On regaining her health, Lucy began to apply the method to others. An advertising flier in the collection of the Vermont Historical Society notes that she began her practice in 1842 at age 23.5 The earliest contemporary account of her activities appeared in a Brandon, Vermont newspaper, Voice of Freedom, on January 29, 1846. Then 26 years old, she was living in Moriah, New York, and conducting clairvoyant diagnostic sessions for paying clients. The mesmerism was being performed by another Vermonter, Charles Rawson Cooke of Morristown, whom Lucy would marry on April 14, 1846.

“While in this state she professes to be able to examine the human system in all its parts – to describe the internal organs with the same precision as when laid open to view, by the anatomist – telling the condition of the lungs, heart, stomach, liver, etc.; detecting any and all disease that may be lurking in the system, and prescribing a remedy for such as can be cured.”6

The notion of a clairvoyant physician was not as unusual in 19th-century America as it might seem. First introduced by a Frenchman, Charles Poyen, in 1836, mesmerism quickly became a popular form of entertainment in which people were placed in a hypnotic trance. The process was often tied to another cultural fascination, spiritualism, or communication with the dead. While Sleeping Lucy never represented herself as a spiritualist, she was undoubtedly familiar with contemporary lecturers such as Andrew Jackson Davis (1826-1910) and practicing Vermont spiritualists such as Achsa White Sprague (1827-1862) of Plymouth. That said, Lucy cannot be dismissed as an imitator - Davis would not start “magnetic healing” until 1844, and Sprague would not claim to have been healed by spiritual intercession until 1847. If anything, we must ask whether any of these people were emulating Lucy rather than the reverse.

By 1848, Charles Cooke had purchased the Forrest House hotel in Hammondsville, a hamlet of Reading, Vermont, on what is now Route 106. The 1850 Federal Census lists his occupation as “physician”; however, he possessed no medical qualifications. In all probability, the title added an air of legitimacy to both the mesmeric process and, given the societal mores of the time, the relationship between the mesmerist and the medium. Americans had a prurient fascination with the idea of a man placing a woman in an altered state of consciousness, which only enhanced the entertainment value of the experience. Lucy’s services appear to have been in great demand, as the Cookes acquired a second home nearby and commissioned two large portraits now in the collection of the Vermont Historical Society. A daughter, Julia Ann, was born in 1851.

Their time in Reading was brief. Charles Cooke died of typhoid fever on August 18, 1855, leaving Lucy an estate valued at $7,0007 (acquired more through his wife’s labors than his own). Lucy sold their Reading properties and moved with Julia to Montpelier, settling at 12 Liberty Street.

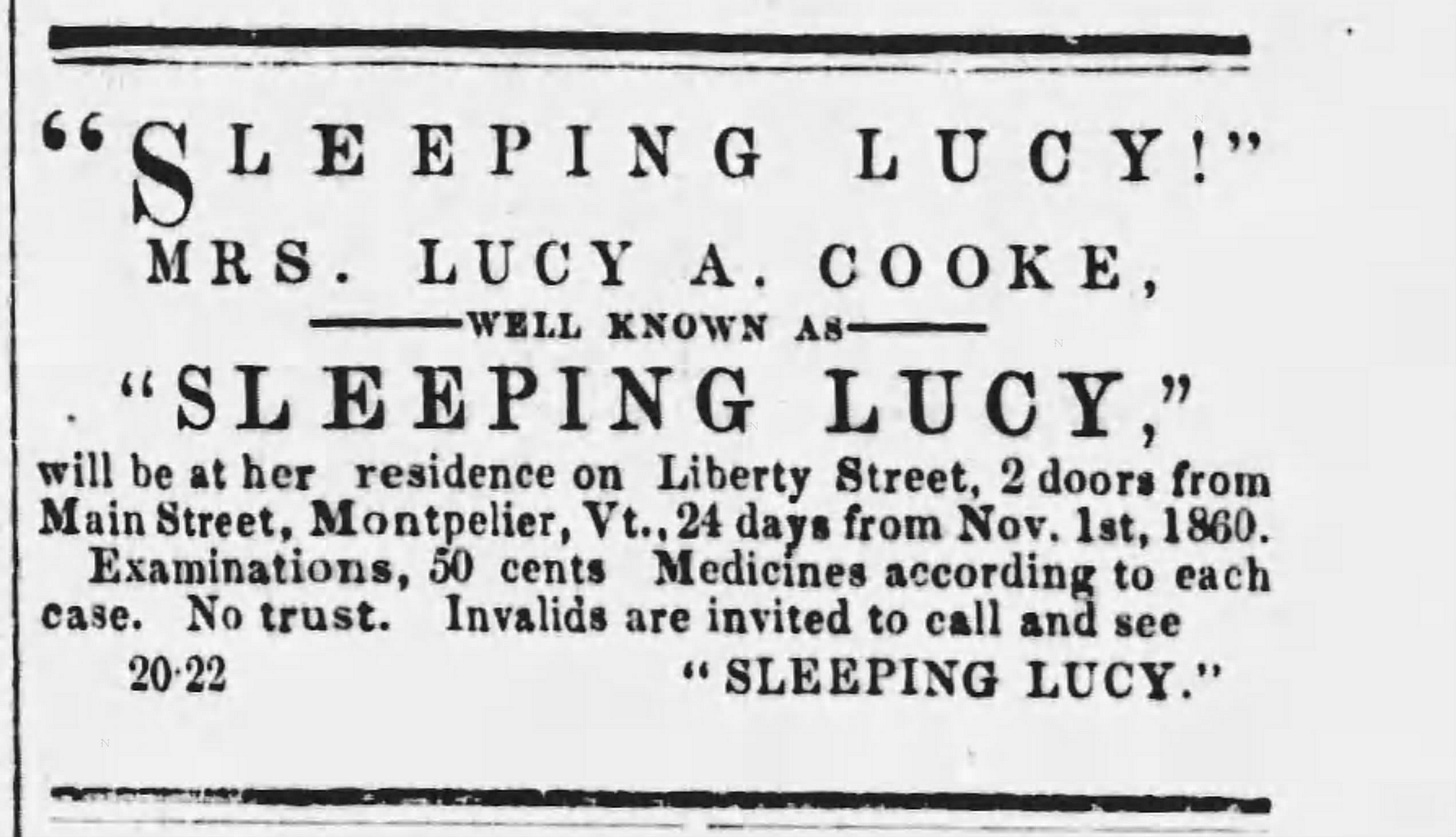

By 1860 the Cooke household consisted of Lucy (38), “clairvoyant and physician”, her daughter Julia Ann (8), Sidney E. Emmerson (36), physician, Hannah Jones (50), domestic, and Sarah G. Cloughlin (35), tailoress.8 Like Charles Cooke, Emmerson was probably her mesmerist, and Sarah Cloughlin a boarder.

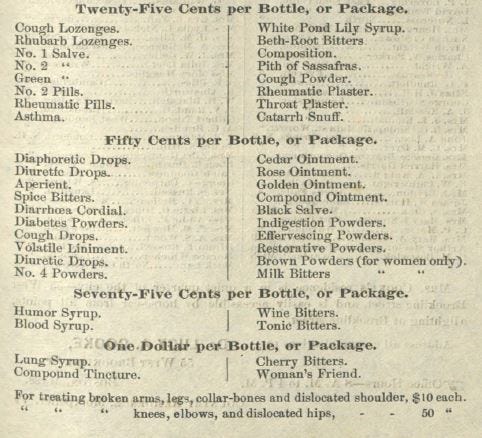

While living in Montpelier, Lucy made periodic trips to Boston and Springfield, Massachusetts, where she booked hotel rooms and consulted with paying patients. Legitimate or not, the clairvoyant “examinations” were a platform through which she could market an extensive list of remedies of her own making. Lozenges, drops, salves, and bitters could all be bought at prices ranging from $0.25 to $1.00 per bottle or package.

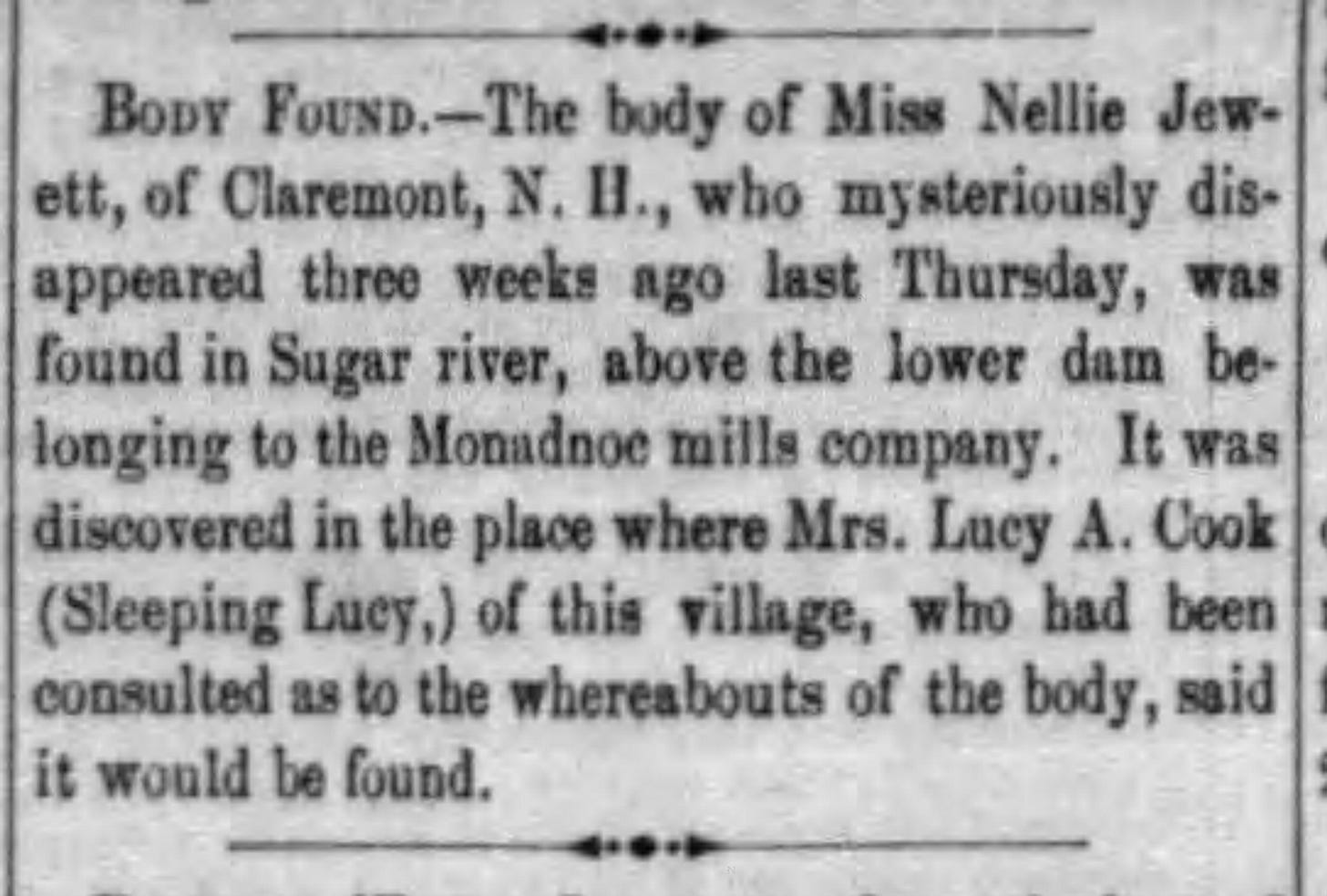

Lucy never represented herself as a spiritualist or communicated with the dead. The bulk of her practice involved diagnosing sickness and setting broken bones. She would also locate lost possessions and, on occasion, missing people. In 1872, she was consulted in the case of Nellie Jewett, a missing woman from Claremont, New Hampshire, and is said to have given the authorities the precise location where the body was found. In 1874, she provided similar services in the case of Daniel Gates of New Lebanon, New York.

Lucy and Julia left Montpelier for Boston in October 1875, settling first at 55 West Brookline Street in the South End. Lucy appears to have prospered in Boston, just as she had in Reading and Montpelier.

On June 3, 1885, Lucy, then 66, married Everett Willard Raddin, a 29-year-old former tobacconist probably serving as her mesmerist. Raddin came with a checkered business history that included at least one bankruptcy. Lucy purchased a home at 9 Forest Street in the Porter Square neighborhood of Cambridge. In 1890, Greenough’s Cambridge Directory listed Raddin’s occupation as “physician,” which suggests that Lucy, then 70 years old, was still practicing.9

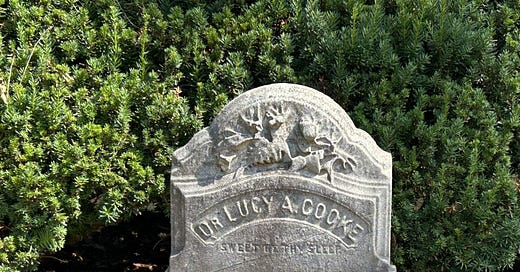

Sleeping Lucy died of colon cancer on May 24, 1895. Her obituary in the Boston Globe notes that she had been ill for about a year but continued to practice until the last few weeks of her life.10 She is buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery with a headstone identifying her as Dr. Lucy A. Cooke and the inscription “Sweet be Thy Sleep.”

Everett W. Raddin died on October 1 1916 and is buried next to Lucy in Mt. Auburn Cemetery. A wealthy man, thanks to his wife’s labors, his will included several private bequests with the residue of the estate offered to Cambridge City Hospital on the condition that they display a portrait of Lucy in some public area. This was presumably the portrait presented to her by friends and admirers in 1880. If the hospital trustees chose not to accept the gift, it was to be offered to the Kellogg-Hubbard Public Library in Montpelier under similar terms. The disposition and present location of the portrait are unknown.

Sleeping Lucy was the subject of considerable skepticism throughout her career, and we are left to decide whether she was indeed the clairvoyant she represented herself to be or simply an artful performer. She was certainly a savvy businesswoman with a large and loyal following and a gift for self-promotion. She must also have possessed a comprehensive knowledge of botanical medicine. At least three of her brothers, Luther Ainsworth, Jr., George Washington Ainsworth, and Milo Daniel Ainsworth, also dabbled in “roots” and called themselves doctors at various times, yet none claimed to be clairvoyant. In the end, perhaps the legitimacy of Sleeping Lucy’s clairvoyance is of secondary importance. Mesmerism was a means to an end, enabling an impoverished Vermont farm girl to rise above both a lack of formal education and the societal constraints imposed upon women in the 19th Century.

Mark Bushnell, Hidden History of Vermont (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2017) 83-86.

Paul Heller, “Sleeping Lucy” Montpelier’s Clairvoyant Doctor, Barre-Montpelier Times Argus October 27, 2018.

“Vermont, U.S.., Wills and Probate Records, 1749-1999 ", database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9084/images/007714767_00110?pld=1157738: accessed October 12, 2024) database entry for Jacob Ainsworth, died Washington County, February 4, 1828.

Lucy A. Cooke, The Morning of Life (Privately printed, 1884). Collection of the Vermont Historical Society.

Advertising Flier for Sleeping Lucy of Montpelier, Vermont, circa 1878. Collection of the Vermont Historical Society.

F. J. Farr, “Nervous Susceptibility - Clairvoyance,” Voice of Freedom, January 29, 1846, (https://www.newspapers.com/image/168438300).

“Vermont, U.S.., Wills and Probate Records, 1749-1999 ", database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9084/images/007714646_01347?pld=1230566: accessed October 9, 2024) database entry for Charles R. Cooke, died Windsor County, August 18, 1855.

1860 U.S. census, Washington County, Vermont, population schedule, Montpelier, p.61, dwelling 471, family 494, Lucy A. Cook; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed October 13, 2024); citing NARA microfilm publication M653, roll 1324; page 69.

The Cambridge Directory of the Inhabitants, Institutions, Manufacturing Establishments, Societies, Business, Business Firms, State Census, Map, Etc., Etc., Etc. (Cambridge, W. A. Greenough & Co., 1890), p. 413, entry for Everett W. Raddin.

The Boston Globe, May 25, 1895, (https://www.newspapers.com/image/735422196)

What a powerful reminder of how unconventional paths can lead to groundbreaking impact! Thank you for sparking an interest -- I am now curious to learn more!

Fascinating! Thank you.