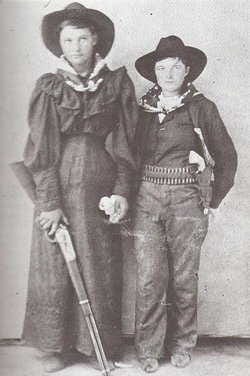

Having looked at Yankees who left the farm to find success in the West, it is interesting to consider the reverse – Westerners sent east. The Town of Sherborn was briefly home to two young women who, rightly or wrongly, became legends of the Old West. While “Cattle Annie” McDoulet and Jennie “Little Britches” Stephenson may have failed as outlaws, they were fully embraced by both the American press and Hollywood, resulting in a tangled mélange of truth and fantasy that is almost impossible to separate 119 years later.

“Cattle Annie” was born Anna Emmaline McDoulet in September 1880, probably in Sugar Creek, Kansas. Her father, James Clemens McDoulet, was an attorney and, according to newspapers of the period, a circuit-riding Methodist preacher. The McDoulet parents were studies in contradiction. In April of 1882, James McDoulet and one Theodore Robins were arraigned and charged with “sending a threatening letter to Henry Lawrence for the purpose of extorting money”1. The prosecution’s witness failed to appear, and the case was dropped. In September 1895 Anna’s mother, Rebecca McDoulet, was arrested in Ponca City and charged with stealing clothing. By 1884 the family was living in Coyville, Kansas (about 85 miles east of Wichita) with James keeping a law office in the nearby town of Fall River. In about 1893 they relocated again, this time to Skiatook, in what was then the Cherokee Nation. Prison records indicate that 13-year-old Anna washed dishes at a hotel and worked briefly for the family of a local doctor.

It's not clear where Anna McDoulet and Jennie Midkiff met. Born Jennie Stephenson in 1879 in Barton County, Missouri, Jennie’s father Daniel Stephenson was a farmer. When she was about 8 the family left Missouri for the Indian Territory, settling first in Seneca, later in the Creek Nation, and ultimately in Pawnee, Oklahoma (about 50 miles west of Skiatook). In March 1895, 14-year-old Jennie ran away from home and married a 33-year-old horse trader named Benjamin Midkiff. The marriage certificate, issued in Perry, Oklahoma, gives her age as 18. The union lasted six weeks.

At some point in the summer of 1895, the girls took up a vagrant lifestyle, traveling on horseback through Indian Territory, wearing men’s clothing, and breaking the law by selling whiskey to the Indians. On 19 August 1895, they were arrested in Pawnee. It was at least their third encounter with the authorities. An account in The Claremore Progress of 24 August 1895 notes that several shots were exchanged before their surrender. It further states:

Jen Medkiff is a cousin to Bill Dalton, and has a huge pistol strapped on her most of the time. The girl says that if they had known that only four officers were surrounding them when they were captured they would have fought their way out.2

This is the first known reference to a connection between Jennie Stephenson and famed outlaw Mason Frakes Dalton, also known as William Marion or “Bill” Dalton.

Widely reported by the American press, the capture of Anna McDoulet and Jennie Stephenson was even picked up by Britain’s Shepton Mallet Journal, whose primary interest seems to have been that the “juvenile new women” rode astride rather than side-saddle.

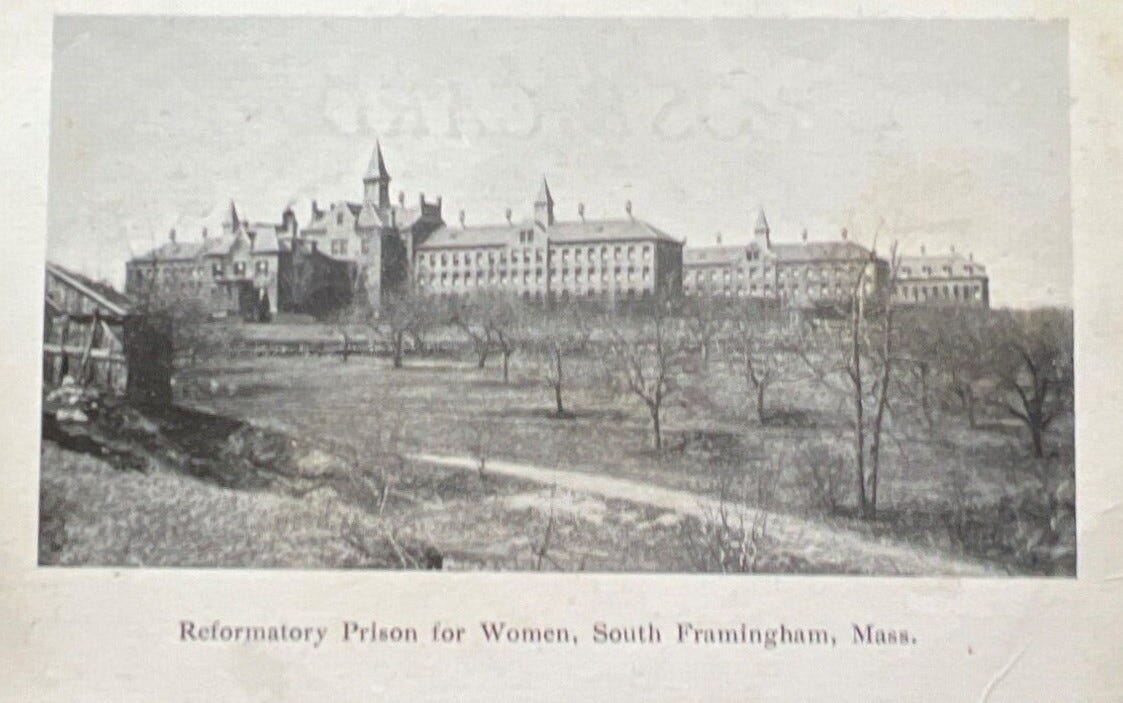

On 27 August 1895, Anna McDoulet was sent to the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women, situated in a part of Sherborn that would later be ceded to Framingham. She received consecutive one- and two-year sentences for “introducing ardent spirits into Indian Territory”. Jennie Midkiff’s sentencing was delayed while she testified before a Grand Jury in Perry, but, on 11 November 1895, she received a one-year sentence for the same crime.

Was Jennie Stephenson a Dalton cousin? I could find no evidence to substantiate the allegation but both families came from Missouri, so it’s at least theoretically possible. The Dalton Gang in its original configuration included four Dalton brothers, Bob, ”Grat”, Emmet, and Bill. They operated between 1890 and 1892, robbing banks and trains between Kansas and California. Bob and Grat were killed, and Emmet captured, in a botched robbery of two banks in Coffeyville, Kansas on 5 October 1892.

After his brothers’ deaths, Bill Dalton teamed up with another notorious outlaw, Bill Doolin, operating largely in and around Oklahoma. Dalton was killed near Ardmore on 8 June 1894, well before Anna and Jennie took up their wanderings. The gang, known as the Wild Bunch (as was Butch Cassidy’s entirely separate gang in Wyoming), was still active under Doolin’s leadership, and the girls are said to have acted as their lookouts, with Doolin giving Jennie her nickname of “Little Britches.” As with Jennie’s family ties to the Daltons, there is no evidence to prove that Anna and Jennie were ever involved with any of these people – and yet there is just enough anecdotal information to leave us wondering. The following story, which misidentified Anna’s mother Rebecca as “Jennie”, ran in the Woodward News on 24 January 1896, while Anna was at the Reformatory.

The press embraced the story of Cattle Annie and Little Britches from the start and concocted multiple romances between the girls and members of the Dalton-Doolin Gang including Bill Dalton, Bill Doolin, and George “Red Buck” Waightman. One version, first printed in The Burlington Republican of 5 September 1895, states that Anna was the sweetheart of Bill Doolin with Jennie similarly enamored of the already deceased Dalton. A second version, in The Kildare Journal of 6 September 1895 reports that Anna “fell desperately in love with Outlaw Buck Weightman and accompanied him on several excursions”3. Whether Anna and Jennie were actually with them or not, the end was near for the Doolin-Dalton Gang, both “Red Buck” Waightman and Bill Doolin would be killed in 1896.

Jennie (Stephenson) Midkiff was discharged from the Reformatory on 7 October 1896 and is said to have returned to Oklahoma, where she effectively disappeared. There are rumors that she married again and lived a law-abiding life in Tulsa, but as with so much of the story, there is no credible evidence to substantiate this. She does not appear to have rejoined the otherwise law-abiding Stephenson family, who remained in Pawnee through 1910 before relocating to Idaho.

Anna McDoulet was discharged on 18 April 1898 and may have worked briefly as a housekeeper for a woman in Sherborn named Mary Daniels. If this was the case, the family was almost certainly that of Frank T. Daniels, then the owner of Stannox Farm at what is now 11 Nason Hill Road.

On 13 March 1901, Anna married Earl Frost, a laborer in Perry, Oklahoma. They had two sons before divorcing around 1905. Around 1910, she married again, to Whitmore Roach, a house painter living in Oklahoma City. Anna Emmaline (McDoulet) Roach was 98 years old when she died in Oklahoma City on 7 November 1978. Her obituary notes only that she was a retired bookkeeper and a member of both the American Legion Auxiliary and the Olivet Baptist Church. She is buried with her second husband and one son in Oklahoma City’s Rose Hill Burial Park.

The story was two decades old when Hollywood first picked it up in The Passing of the Oklahoma Outlaws, a silent film produced by the Eagle Film Company in 1915. The film was directed by famed Marshal Bill Tilghman, whom legend credits with bringing in both girls after a blazing gun battle in which he shot Jennie’s horse out from underneath her. Contemporary accounts of the incident credit the arrest to Deputy Marshals Steve Burke and E. W. Kinan, with no mention of Tilghman’s involvement, but neither Tilghman nor his cinematic successors seem to have been overly concerned with veracity.

In 1949 Columbia Pictures released “The Doolins of Oklahoma” starring Randolph Scott as Bill Doolin, Virginia Huston as his girlfriend Elaine Burton, and Dona Drake as “Cattle Annie”.

Lamont Johnson’s 1981 film Cattle Annie and Little Britches featured Burt Lancaster as an aging Bill Doolin, with Amanda Plummer and Diane Lane as Anna and Jennie. This version of the story overlooked the fact that Doolin wasn’t aging, he was a relatively youthful 38-year-old at the time of his death.

To be fair, accuracy is difficult when so few facts are known, and perhaps it never mattered. Anna and Jennie rode into Western lore as the characters people wanted them to be. As reporter Maxwell Scott observed in John Ford’s classic The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “This is the West, Sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”. The only people who didn’t want the legend of Cattle Annie and Little Britches were the girls themselves, neither of whom seem to have spoken publicly, let alone sought publicity for their youthful misadventures.

Greenwood County Republican, 7 April 1882

The Claremore Progress, 24 August 1895

The Kildare Journal, 6 September 1895