One of the more intriguing chapters in the history of Vermont is the “gold rush” which took place in the second half of the 19th Century. While gold was actively mined in several parts of the state, much of the activity was clustered in the Windsor County communities of Bridgewater and Plymouth.

Earlier discoveries of gold in the towns of Somerset and Newfane are mentioned in Charles Baker Adams’ First Annual Report on the Geology of Vermont, published in 1845, but the real impetus for Vermont’s “gold fever” was the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California on 24 January 1848. The first Vermont newspaper coverage of the discovery known to me is an article in the Vermont Watchman and State Journal of 21 December 1848. The date of its publication suggests that it took about 10 months for the news to filter back to the Green Mountains. Over the next several years some 11,000 Vermonters braved the considerable risk and hardship of a five or six-month voyage to the gold fields.

Both the relatively late date at which the news reached Vermont and the extent of the ensuing journey resulted in most of Vermont’s Forty-Niners arriving on the tail end of a mass migration numbering in the order of 300,000 people. Failing to find the fortunes they were seeking, many came home. By 1851 there were a number of returned Forty-Niners in Vermont with at least a basic comprehension of geology and mining technology.

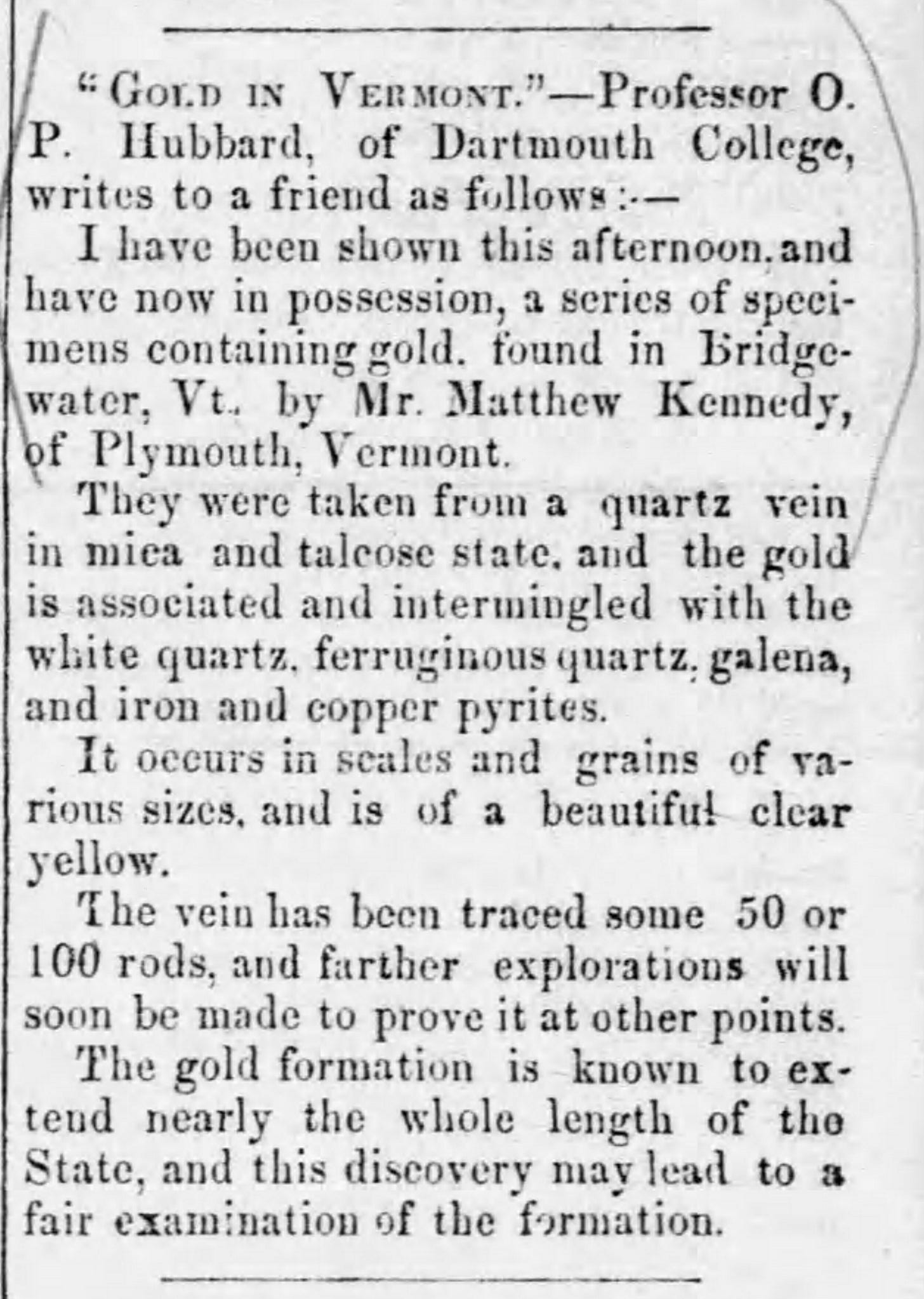

In August of 1851 Matthew Kennedy, a resident of Plymouth, visited his son Matthew Edwin Kennedy at the latter’s home on Chateauguay Road in the neighboring community of Bridgewater. The senior Matthew Kennedy is identified by several sources as a returned Forty-Niner, but I can find no evidence to substantiate that allegation. He is known to have owned a lime kiln and thus probably had some basic knowledge of geology. While hunting for bees, he noticed some interesting quartz specimens in the bed of a creek he was crossing. Putting them in his pocket, he later brought them to Dr. Oliver Payson Hubbard, Professor of Chemistry, Minerology, and Geology at Dartmouth College. Hubbard identified them as gold-bearing ore but appears to have kept the discovery to himself until Kennedy had purchased the land on which he had made his discovery.

On 9 September 1852, Kennedy bought 99.75 acres from George Williams and Ephraim Bryant of Hartland for $700. On the same day, he conveyed a half interest in the property to Ira Smith of Westminster for $4,000. With ownership secured, he seems to have authorized Dr. Hubbard to announce the discovery, as evidenced by this article in the Middlebury Register of 2 December 1852. Kennedy may have felt that the imprimatur of a respected professor would add credibility and ultimately value to his acquisition.

Kennedy and Smith worked the land for several years before apparently concluding that the rewards didn’t justify the effort required. On 10 August 1854, they sold the land to Ira F. Payson of New York for $11,000, taking back a mortgage of $9,000 and being promised an additional $6,000 in the stock of Payson’s new company, the Vermont Gold Mining Company, which would be incorporated on 14 November 1854.

Ira Payson was the first in a succession of interesting characters that would make their way onto the local scene. Probably born in New York in 1822, by 1850 he was employed as a merchant in Flint, Michigan. In 1853, being then of New York, he was granted a patent for an improvement in soap ingredients. On 22 July 1854, the Danville North Star reported that “Captain Ira F. Payson of N. Y. having bought these mines, for the last three or four weeks from 30 to 50 workmen, several of whom are experienced miners, have been digging into, and examining the premises, where gold has been discovered; about which our readers have heretofore heard. And what is particularly gratifying, the result thus has proved entirely satisfactory to those engaged in this enterprise.”

People tend to think of gold mining in terms of placer mining, which is the traditional gold pan and sluice box method utilizing water to separate gold particles from river gravel. The mining taking place in Bridgewater was primarily lode or hard rock mining, in which veins of quartz were excavated and crushed to extract minute quantities of gold. As a result, in addition to the various mine shafts, the local landscape is dotted with test pits of varying sizes.

Once removed from the ground; the ore was usually piled nearby for transportation to a crusher. As mines were found to be unproductive many such piles were simply left in place and these tailing piles, along with evidence of an old roadway, are a good way to identify abandoned gold mines.

Ira Payson’s success was short-lived. By 1855 he had sold his interest to three New York investors and William Billings, of Woodstock. Matthew Edwin Kennedy would later say of Payson “he lived at Woodstock, had a fine pair of horses to drive up here, and $8 brandy was none too good for him to drink. But the head man among the miners died after a while, the others didn’t seem to know much about the business, the men in the company got disgusted and the thing stopped.” Payson returned to Michigan, and then moved to Colorado, from whence he was appointed an Assistant Quartermaster in the U.S. Cavalry by Abraham Lincoln. He died of a compound leg fracture in Alexandria, Virginia in 1864 and is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Matthew Kennedy foreclosed and got the land back. In 1859 he sold it again, this time to Alexander Taggart of Goffstown, New Hampshire. He then left Vermont for a farm in Iowa. Taggart, also said to have been a returned Forty-Niner, worked what would later be known as the Taggart Mine from 1859 to 1879, when he sold it to the Green Mountain Gold Mining Company.

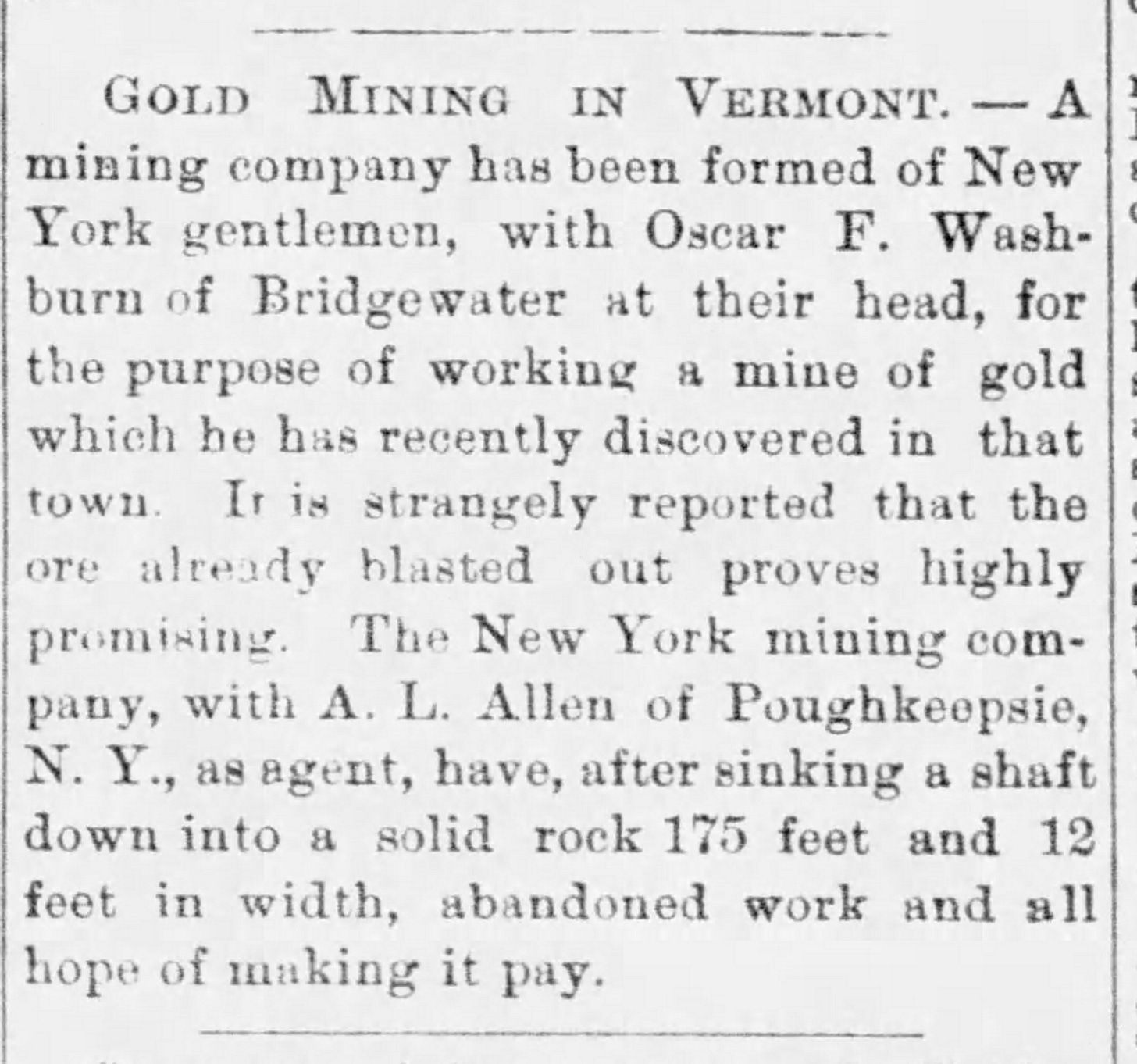

In 1864 another colorful character arrived in Bridgewater. Oscar Fitzland Washburn was born in Goshen, Massachusetts in 1825. The 1860 Federal Census lists him as a watchmaker in New York and, by 1864, he was in Bridgewater functioning as the manager of the Quartz Hill and Pioneer Gold Mining Company. A contemporary account characterized him as “a gentleman of good education and refined culture, but somewhat erratic in his views”.

Washburn dammed the brook that bears his name today and used water to power his ore crusher until a flood in October 1869 washed the entire operation away. He spent the next five years working as a laborer in a North Carolina gold mine, but returned to Bridgewater in 1888 and worked the Quartz Hill Gold Mine on his own until at least 1900. At some point thereafter he returned to his hometown of Goshen, Massachusetts, where he died on 7 June 1912.

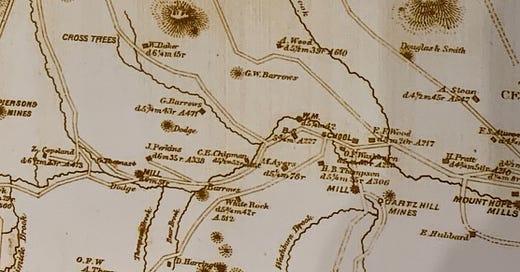

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, various companies continued to mine in Bridgewater, including the Windsor Gold & Silver Mining Company and the Green Mountain Gold Mining Company. It’s difficult to say much about these companies or even determine their exact locations. Some had more than one mine and, with the failure of one company, another would frequently acquire the assets, thus any given mine might have been operated under different names at different times.

The 1890s brought a resurgence of interest in Bridgewater’s mining potential and still more colorful characters. Frank S. MacKenzie, owner of the Bridgewater Woolen Mill and one of the few locals to catch “gold fever” was also President of the Mineral Hill Gold Mining Company. The Honorable Edgar S. Moulton was President of the Ottauquechee Gold Mining Company while actively serving as the Mayor of Fitchburg, Massachusetts.

The shadiest of Bridgewater’s gold miners was Major Edward Le Mesurier Witten Hoar. Born in 1840 as plain Edward Hoar, a Welsh gardener’s son, he enlisted in the Royal Engineers as a young man. While stationed in London the young soldier became enamored of a rising young comic opera singer, Elizabeth Knibbs, who performed under the stage name Lizzie Lemure. They married in England, and, in 1871, Lizzie gave him the funds to buy his way out of the army. Corporal Hoar pocketed the money, deserted from the Royal Engineers, and left England for America. Lizzie followed, and they settled in Chicago where he worked as a civil engineer. In 1880 the still childless couple brought Lizzie’s 16-year-old niece, Emily Knibbs, over from England. Edward seems to have taken an active interest in the young lady as, not long thereafter, she was found to be in what the Victorians termed “a delicate condition”. The lurid divorce proceedings were extensively covered by the American press and constitute Edward Hoar’s only legitimate claim to fame. Hoar, his new wife Emily, and their infant daughter Edna decamped for Bayonne, New Jersey, where he continued a civil engineering practice. In 1901, having reinvented himself as a retired British Army officer and international mining expert, Major Edward Le Mesurier Hoar arrived in Bridgewater, where he established the Sunny Crest Mining Company and later the Northeastern Mining Company. Hoar also built a large gold crusher in Chateauguay and a nearby dormitory to house Italian miners.

By 1910 both the money and the Major had run out, and the property, consisting of the Elisha Perkins and Freeman Dimick farms in Dailey Hollow, was sold to the last figure in the story, Dr. Benjamin Fagnant. Originally from Quebec, Fagnant was a physician practicing in Springfield, Massachusetts, who, with his brother Joseph, had been in Bridgewater since at least 1900 operating the Federal Gold Mining Company, the Oriental Gold Mining Company, and finally, the Canadian -American Gold Mining Company.

Dr. Benjamin Fagnant died in Springfield, Massachusetts on 19 August 1916, and, with his passing, the era of gold mining in Bridgewater came to an end. His brother Joe Fagnant remained in town until at least 1919, still professing his belief in the profitability of the mines, although I suspect very little actual mining had happened since about 1913. In 1924 the Town of Bridgewater moved to auction the land held by the Ottauquechee and Canadian-American Gold Mining Companies for unpaid real estate taxes going back to 1919. The auction never took place, and that property, encompassing 570 acres, was acquired by a local family.

“Major” Edward Hoar died at his Manhattan home in 1913 and is buried with his daughter Edna (Hoar) Mass and her family in West Woodstock’s Riverside Cemetery. The machinery was removed from his large ore crusher in 1919 and used for other purposes. The structure itself collapsed in the early 1920s.

I’ve been told by several people that the “Gold Rush” in Bridgewater was a hoax brought about when a canny farmer salted a hillside with a few shotgun barrels of gold dust. That myth doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Even the most ignorant of hard rock miners weren’t looking for scattered nuggets, and the best of hoaxes couldn’t have endured for more than six decades. That leaves us with the enduring question of how so many people could have spent so much time and money digging for something with absolutely no evidence of its existence in any useful quantity. The answer, I think, is that with the exception of Matthew Kennedy and Frank MacKenzie, none of the people involved were local. They were all outsiders - restless, clever men, some with dubious ethics, who came looking for their El Dorado, failed, and moved on to seek it elsewhere. Perhaps the wisest of them all was also the first, Matthew Kennedy, who, on discovering that his gold mine wasn’t panning out, sold it to someone else and bought a farm in Iowa.

Really interesting article. Two years ago my family bought the Freestone Hill property that backs up to Baker Hill Road where the Allen Co. mine was. In fact, the mine shaft that you found is on our land! I just stumbled across it a couple of months ago so I was quite happy to learn the background. Thanks for providing such insightful articles.

Fascinating reading. I have read that the Plymouth Four Corners VT rush was both more populous and profitable. Do you know if that was occurring concurrently with the Bridgewater mines? I believe Plymouth was mostly placer mining as opposed to the hard rock mining occurring in Bridgewater.