Sara Plummer Lemmon

Pioneering Botanist

Stories sometimes change direction and end up in places we couldn’t have imagined. Seemingly unremarkable individuals transcend the event that first brought them to our attention and become a larger story unto themselves. So it was with Sara Plummer Lemmon.

The Historical Society in my hometown of Dover, Massachusetts has in its collection a very old flag measuring 11 feet by 6 feet. It is unusual in that, in addition to 34 stars, the canton features an eagle and, on the fly end, the words “The Constitution” on one side and “Liberty & Union” on the other. The presence of 34 stars suggests that it was made between 1 July 1861, when Kansas was admitted to the Union, and 20 June 1863, when West Virginia was admitted.

Local historian Frank Smith wrote in The History of Dover “In the beginning of the war, when the cry went forth for everyone to show his colors, the women, under the inspiring efforts of Miss Sara Plummer, made a flag with their own hands. As bunting was scarce and high in price consequent to a small supply, the ladies purchased Turkey red and bleached cotton, out of which they made the flag, which was floated during the entire period of the war. The flag bore on the blue not only the required number of stars, but in addition a large eagle.”[1]

Turkey red was cotton dyed with the root of the Rubia plant, commonly used in the making of patchwork quilts. On completion, the ladies’ husbands cut a “Liberty Pole” and placed it on the north side of Farm Street directly opposite the newly built farmhouse occupied by George D. Everett and his wife Martha. A cord was hung linking the pole to the attic window of the Everett house, and the flag was suspended across Farm Street in celebration of every Union victory from Shiloh to Lee’s surrender.

The Plummer sisters, Sara and Martha or “Mattie” were recent arrivals in Dover. Their father, Micajah Sawyer Plummer, had relocated from New Gloucester, Maine at some point just prior to 1860, and owned a small grocery store near the intersection of Springdale Avenue, Farm Street, and Main Street. Of Micajah and Betsey (Haskell) Plummer’s five children, their oldest son, Charles, had already left Maine for Illinois and later Iowa, and their second son, Osgood, was living in Philadelphia. Sara and Mattie, and their younger brother, Seth, had come south with their parents. On 23 June 1861, Mattie Plummer married George Draper Everett, a merchant operating a grocery and grain store out of their Farm Street home.

The Plummer family placed a high value on education, as Sara had studied at Ladies’ Collegiate Institute in Worcester, Massachusetts (1857) and both Sara and Mattie had attended Westbrook Seminary in Portland, Maine (1858). In 1861, with Mattie married, Sara moved to Brooklyn, New York, where she continued her education at Greenleaf Female Institute and The Cooper Union, graduating from the latter with honors and a double degree in chemistry and physics. All of this was accomplished while nursing wounded soldiers at Bellevue Hospital and later teaching elementary school. Perhaps exhausted by the pace of her activity, her health was compromised by an attack of measles and later pneumonia.

In 1869, with her lungs permanently weakened, Sara moved to California in search of a drier and more hospitable climate. While the transcontinental railroad was completed in that year, she made the journey by sea, traveling alone from New York to Panama, across the Isthmus, and up the coasts of South and North America to San Francisco. Ultimately settling in Santa Barbara, she opened a stationary store and established a lending library that would eventually become the city’s first public library. She also developed a passion for botany, took an active role in the Santa Barbara Society of Natural History, and began painting the flowers and plants of her adopted state.

Sara’s intellectual and artistic trajectory soon brought her to the attention of another rising botanical star, John Gill “J. G.” Lemmon. A native of Michigan, Civil War veteran, and survivor of Andersonville, Lemmon had come to California to recuperate from the mental and physical horrors of his wartime experiences. Marrying in 1880, Sara and J. G. spend their honeymoon in Tucson, Arizona scaling the highest mountain in the Santa Catalina range, a 9,171-foot peak that would later be named Mount Lemmon in Sara’s honor.

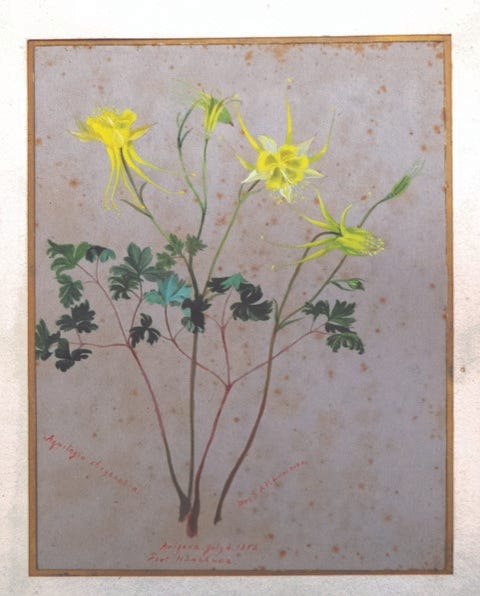

The couple spent the rest of J. G.’s life searching for and cataloging the botanical specimens of the West Coast, with Sara providing illustrative paintings. Their collection, the Lemmon Herbarium, was ultimately donated to the University of California at Berkeley. Sara’s painting of Golden Columbine (Aquilegia chrysantha) is shown below:

J. G. Lemmon, whose health had been irreparably damaged by his Civil War experiences, died in 1908. Sarah never recovered from the loss of her beloved partner, ultimately dying of senile dementia in 1923. Both are buried in Oakland California’s Mountain View Cemetery, beneath a headstone marked “Partners in Botany”.

George and Mattie (Plummer) Everett operated a feed and grocery store from their home at 56 Farm Street in Dover for many years. Both served the Town as well, George as Selectman and Treasurer, and Mattie as Superintendent of Dover’s schools for ten years. Mattie was an early and active advocate for women’s rights, and a frequent presence at state and district conferences. George died in 1904 and Mattie in 1926, having lived long enough to witness the passage of the 19th Amendment and no doubt receiving the satisfaction of casting her own votes in the elections of 1920 and 1924. Both are buried in Dover’s Highland Cemetery.

Martha (Plummer) Everett’s grandson, Harold Bernard St. John (1892-1991) would follow very much in his aunt Sara’s footsteps as a distinguished field botanist, professor of botany, and curator of the herbaria at the University of Hawaii Manoa from 1929 to 1958. It was he who donated the flag, lovingly preserved by his mother, to the Dover Historical Society, in 1965.

Author Wynne Brown has recently written a biography of Sara Plummer Lemmon titled “The Forgotten Botanist - Sara Plummer Lemmon’s Life of Science & Art” which can be purchased here:

https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/bison-books/9781496222817/

[1] Smith, Frank. History of Dover, Massachusetts as a Precinct, Parish, District, and Town. Dover, Mass: Published by the Town, 1897) p. 309.